HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

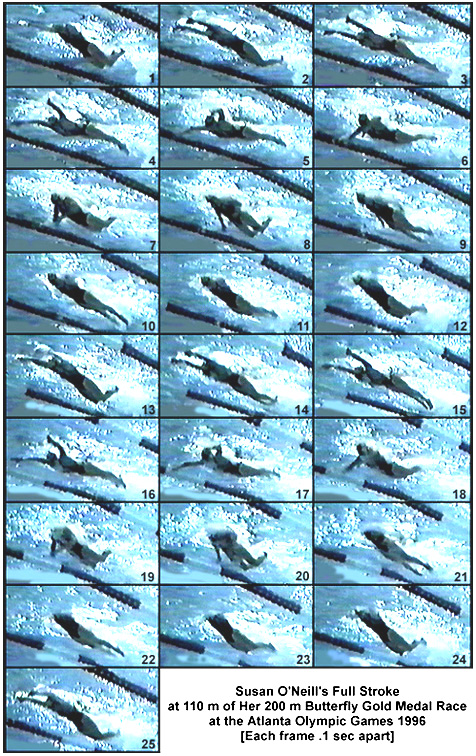

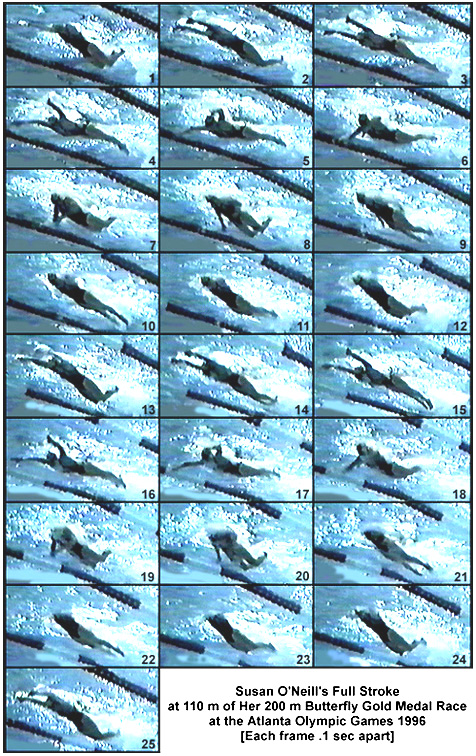

SUSAN O'NEILL'S FULL STROKE AT 110 m OF HER 200 m BUTTERFLY GOLD MEDAL RACE AT THE ATLANTA OLYMPIC GAMES 1996

Each frame is .1 second part. This sequence contains a non-breathing stroke followed by a breathing stroke. The reader should also refer to the other analyses of Susan O'Neill's stroke in the same race.

At this stage of the race, Susan O'Neill had turned at the 100 m in 1:00.66 which was .82 seconds faster than Mary T. Meagher's 1981 record split. By the end of this lap, her time slows to .07 seconds slower than MTM's record pace.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The hands are just entering and are slightly wider than shoulder width. The knees have dropped in preparation for the kick. The preparatory kick movement also drags the hips lower upsetting streamline. This suggests the kick is too large.

- Frame #2: The hands continue inward after the entry as a result of the inertia of their recovery path. The feet are more than half-way through the kick and the hips have elevated as a consequence of the kick's force.

- Frame #3: The hands scull outward, in a movement similar to that of an early stage in a breaststroke pull. This occurs to halt the shoulders diving downward. However, the kick has been so vigorous that the hips have been driven upward. As a counter-balancing movement, the shoulders are forced down more than they should be.

- Frame #4: The outward scull is near completion and the elbows start to bend. As an added action to stop diving, the mid-spine region is arched notably which dissipates the force over a larger area and holds the shoulders at their current level.

- Frame #5: Some medial rotation of the upper arm occurs as the elbows bend. This sets up a moderate degree of an "elbow-up" pulling movement. The head is raised slightly, to bring the body back into streamline, and the back curvature appears to have almost dissipated.

- Frame #6: The upper arms are adducted with the hand/forearm surfaces remaining stable to produce large propelling surfaces. The feet are rising to the surface to prepare to kick. This appears to be the end of a very short streamline phase of the stroke.

- Frame #7: The upper arm adduction is completed and the hands are very close together. From here on the arm actions will be extension at the elbows so that the hands will move outward to clear the hips and eventually upward to leave the water. The large kick hypothesis is partly confirmed by this picture as both feet have broken the water surface. Such an action is detrimental as it exaggerates vertical forces (see the hips and knees being forced down and out of streamline) that have to be counter-balanced. Upon reentering the water, the feet will drag air, which decreases their propulsive efficiency through cavitation.

- Frame #8: A partial arm extension is completed but still achieves force production with the hands and forearms. The knees have dropped well down. The feet are re-entering the water as the kick is initiated. The downward drop of the knees is sufficiently severe to cause the head to rise partially out of the water, something that was not evidenced at 65 m in the race.

- Frame #9: The arms "round-out" and extend as the legs kick. At this stage, the kick counter-balances the extraction of the arms and consequently, the knees and hips still stay down and out of streamline.

- Frame #10: The final stage of the kick, and the reflex rigidity that results in the body, produces a close-to-streamline alignment, although it is still angled downward ever so slightly. The top of the head is still on the surface.

- Frames #11 and #12: The legs prepare to kick resulting in the hips and thighs dropping out of streamline.

- Frames #13 to #19: The movements in these frames closely duplicate those in the non-breathing stroke.

- Frame #20: This appears to be a stroke variation, most probably due to raising the head to breathe. The arms are spread earlier in this frame than in frame #8 which is approximately the same stage in the stroke. The feet are also deeper in the water in the same stage of the kick. It is possible that the breathing movement shortens effective length in the latter part of the arm stroke as well as causing the hips and thighs to sink lower when compared to the non-breathing action.

- Frames #21 to #25: See earlier comments for similar stages of the stroke.

It appears that Susan O'Neill's stroke is altering slightly possibly due to fatigue. When compared to the movement pattern displayed in the non-breathing stroke phase at 65 m, the following are possible.

- The magnitude of the arm pulling pattern is declining because the pull starts from a wider position (longer outward scull), the medial rotation of the upper arms is not as pronounced, and the push-back and round-out actions are slightly shorter.

- The stability of the streamline alignment is held for a shorter period and disrupted to a greater degree (the head emerges partly out of the water).

- In the breathing stroke, effective latter-pull length is shortened.

There is evidence in these frames that the kicking movement is too big for the stroke. Rather, than serving to create propulsion and to counter-balance vertical force components, it still provides propulsion but alters streamline noticeably and possibly to the detriment of the swimmer.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.