HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

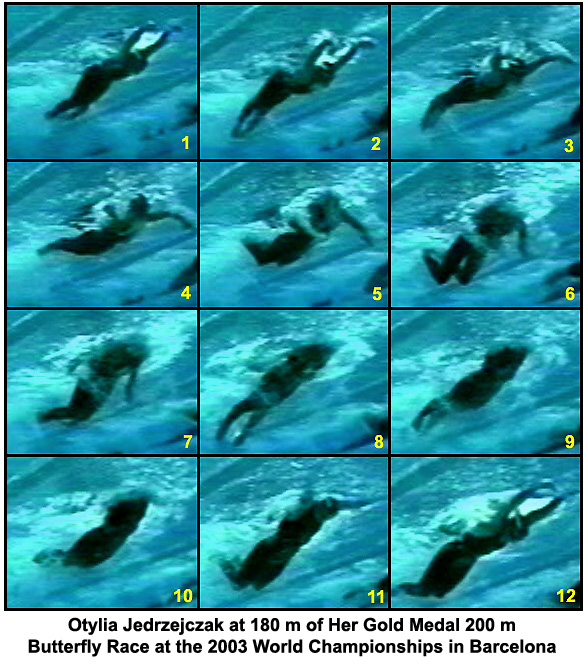

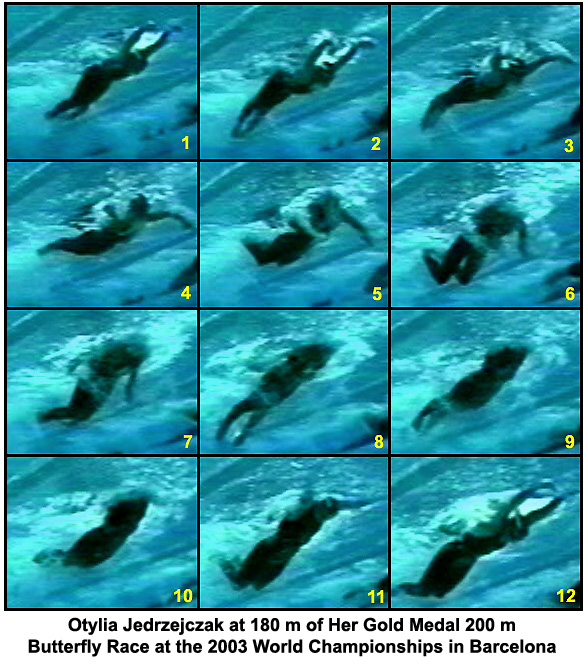

OTYLIA JEDRZEJCZAK AT 180 m OF HER GOLD MEDAL 200 m BUTTERFLY RACE AT THE 2003 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS IN BARCELONA

Each frame is .1 seconds apart. Otylia Jedrzejczak's time for the event was 2:07.56

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

Frame #1: The hands enter flat and almost shoulder width apart. The legs kick down to counterbalance the vertical force components created by the entering hands and arms and the previous lowering of the head and shoulders.

Frame #2: The hands widen slightly as abduction of the upper arms begins. The wrists flex in preparation for propulsion. Drag forces are developed and can be seen by the "white water" on top of the hands. This is an unusual position. It demonstrates an attempt to immediately reposition the arms and hands to develop propulsive movements. It contrasts to the more common action of an outward sculling movement (see Susan O'Neill and Petria Thomas). This writer considers Jedrzejczak's action to be desirable and beneficial. The kick continues to counterbalance the vertical force components of the arms. The shoulders are at their deepest position.

Frame #3: The arm actions are oriented to gaining a propulsive position. The drag turbulence still shows no forward propulsion from this action. The upper arms continue to abduct and medially rotate to produce an "elbows-up" position. The strong vertical force component is partially counterbalanced by the last portion of the kick but the shoulders have risen also because of the arm movement. The body alignment is streamlined.

Frame #4: Both arms develop propulsion. A very powerful abduction of the upper arms produces the force to begin surging the swimmer forward. To this point, the primary reason the hands have increased their width apart is upper arm abduction. In each arm, the humerus pivots in the shoulder joint and therefore, causes an outward sweep of the hand. In this frame, the position of the arms is about as wide as it can be and still remain productive. Once abduction changes to adduction, the forearms need to be in a different position to continue the most effective and largely direct propulsion. The head rises and consequently, the hips begin to drop slightly as a reaction.

Frame #5: Upper arm adduction begins. The hands lead the forearms to attain a position under the swimmer. The largely horizontal drag force that is developed is seen in the turbulence following the simmer's left forearm. The head rises further, the hips and knees drop consequently, and the feet rise preparatory to kicking.

Frame #6: This is most likely the strongest propulsive position in the sequence. The right arm is obscured by its drag turbulence while that of the right arm can be clearly seen and is very large. The hips rise slightly as a reaction to the relatively speaking small vertical fore component of the pulling arms. The kick begins with the knees at their deepest position.

Frame #7: The arms extend back and up as the propulsive pull diminishes and rounding up in preparation to exiting the water conserves momentum. The torso and hips are flat while the knees rise as the feet kick down. The kick cancels the vertical force components developed by the initial stages of the recovery.

Frames #8 through #10: The arms recover. The kick is completed in frame #8 being timed with the extreme vertical force components created by the early recovery. As the arms recovery quickly forward, the hips remain high and the legs prepare to kick to counterbalance the vertical force components of the forthcoming entry and the return of the head and shoulders to underwater.

Frame #11: The head is returned underwater as the arms approach entry. The kick preparation is almost completed.

Frame #12: Entry occurs and the kick commences. The action depicted in frame #1 is repeated as another cycle of stroking begins.

This is a very quick stroking sequence. The absence of unnecessary lateral movements accounts for the reduction in stroke duration and consequential higher stroke rating, a characteristic of Jedrzejczak's swimming.

Although there is some head diving and hip elevation in the stroke, it does not seem to be as exaggerated as it is in other women's strokes. This feature will never be removed from this stroke, but swimmers should attempt to minimize it rather than emphasize it as is demonstrated here.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.