HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

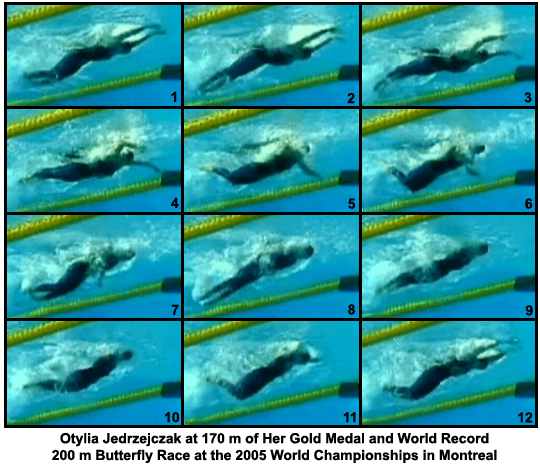

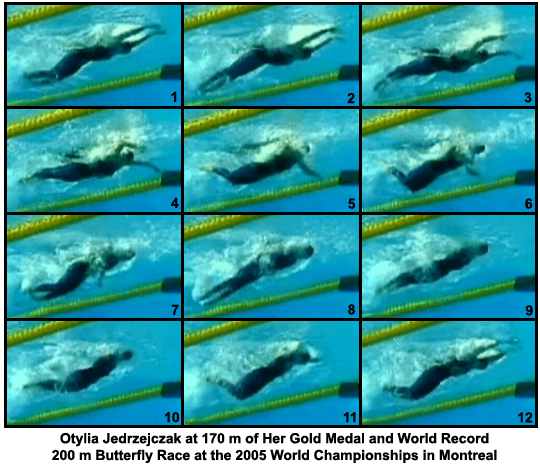

OTYLIA JEDRZEJCZAK AT 170 m OF HER GOLD MEDAL AND WORLD RECORD 200 m BUTTERFLY RACE AT THE 2005 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS IN MONTREAL

The time between each frame is .1 seconds. Otylia Jedrzejczak's time for this race was a new world record of 2:05.61. This sequence is of a non-breathing stroke. It was selected because it represents how the swimmer was performing as she overtook Jessicah Schipper of Australia to win the event by three one-hundredths of a second.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The hands are entering the water. The legs kick to counterbalance the vertical force component created by that entry.

- Frame #2: The arms are completely covered. The head and shoulders have dived deeper in the water as part of the recovery-entry process. The hips have risen because of the kick down and the increased head/shoulder depth. The hands are pitched slightly outward, but much less so than most other female butterfly swimmers.

- Frame #3: The arms begin to be repositioned for propulsion. As the hands spread, the upper arms medially rotate and the elbows flex. The hands turn to face down and backward. The force generated by this arm action, facilitates a lowering of the hips and the beginning of raising the feet preparatory to the next kick. For a female butterfly swimmer, the time from entry to this initiation of propulsion is ~0.2 seconds, a very short interval that borders on direct continuous propulsion. It facilitates a higher than normal rate and is similar to the same stroke phase of Ian Crocker.

- Frame #4: The body is streamlined. The elbows have flexed further and the upper arms are powered by abduction at the shoulder. In this position, the lower arms and hands are likely to be evenly divided between horizontal and vertical force components.

- Frame #5: The arms have used their total surface to generate propulsion. This extremely powerful movement develops a great amount of drag force, which is manifested by a developing large pocket of turbulence forward of the arms. The kick is developing rapidly because the power of the propulsive force takes a sufficiently short time to warrant early preparation for a big kick to counterbalance exiting arms.

- Frame #6: The upper arms have begun adducting toward the sides of the body. The lower arms rotate outwardly in concert with the initiation of elbow extension. Drag-force turbulence is obvious. The knees drop because of a slight flexion at the hips. The head remains oriented to the pool bottom.

[The cyclic nature of the vertical forces required by conforming to this stroke always generates vertical movements that can only be minimized, not eradicated. Consequently, the head is held in the water but still moves up and down in response to other large vertical forces that are created by the arm action. One reason butterfly swimming is so energy demanding is that a very large amount of effort is dissipated vertically by large powerful movements of the legs and arms designed to keep the swimmer relatively flat.]

- Frame #7: The propulsive surge of the arms in this part of the stroke is near maximum. The resulting momentary increase in velocity also causes the turbulence created by the facial asperities to increase to the extent that the face is obscured by the "white water". The kick has been initiated to be timed with the maximum vertical force component of the exiting arms. The torso and head are quite flat while the legs are involved totally in the kick.

- Frame #8: The arms exit the water. The kick is completed to counterbalance the exiting arms. The swimmer's head and torso are streamlined.

- Frame #9. The swimmer is fully streamlined as the arms sweep wide and relatively low. The feet rise preparatory to kicking.

- Frame #10: The hips drop as the arms sweep forward in recovery and the feet rise prior to kicking. The head remains covered.

- Frame #11: The arms approach entry. The knees drop to place the feet in a position to execute a powerful kick. The head remains low in the water.

- Frame #12: A position similar to that exhibited in frame #1 is assumed.

Otylia Jedrzejczak's stroke has characteristics that are similar to that of Inge de Bruin at the Sydney Olympic Games. There is a minimal inertial lag after entry because the swimmer does not engage in unnecessary repositioning of the arms that are characteristic of many other male and in particular female butterfly swimmers. The turnover (1.2 seconds per stroke cycle) is particularly high for the last lap of a 200 m race and could be a significant factor in Ms Jedrzejczak's ability to come from behind in the final lap to win important races.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.