HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

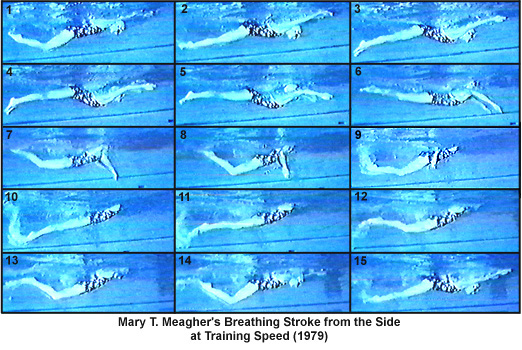

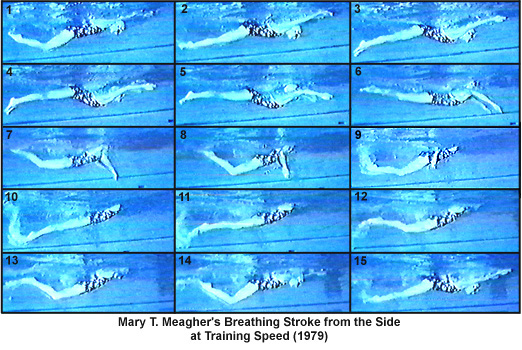

MARY T. MEAGHER'S BREATHING STROKE FROM THE SIDE AT TRAINING SPEED (1979)

This series of frames is taken from one of James "Doc" Counsilman's instructional films. The frame capture speed is not known.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The swimmer kicks down to counter-balance the entering arms. That offsetting action keeps the body relatively straight. The arms enter well in front.

- Frame #2: The kick is almost complete as the arms enter. The hips have risen slightly past horizontal and the shoulders have dropped slightly. The body remains very close to the surface. The shoulders have to drop to allow the arms to achieve an effective propulsive position. The arms are at shoulder width and the hands are immediately rotated outward. In contrast to Susan O'Neill, no inward movement of the hands after entry occurs. The face profile has started to rotate forward. The streamlining and "flatness" (for a butterflier) of this position is noteworthy.

- Frame #3: The kick is completed with the swimmer's buttocks just breaking the surface. The shoulders continue to drop as a reaction to the rising head and hyperextension of the neck. The depth of the kick is not great; the ankles being level with the deepest part of the chest and chin. The arms are repositioned outward to begin an effective pull. The head continues to rise.

- Frame #4: Further hyperextension of the neck forces the shoulders lower and the feet to rise. The upper arms are held particularly "high" while elbow bending begins. Primarily forward propulsion from the arm action commences. When compared to other female butterfliers, it is notable as to how quickly Mary T. commences an effective propulsive force after entry.

- Frame #5: The rising head causes hyperextension of the thoracic region of the spine causing the front of the body to curve downward. The rest of the swimmer is streamlined. Further bending of the arms at the elbows occurs while the upper arms medially rotate keeping the "elbows high."

- Frame #6: The head is raised above the surface, that movement being facilitated by propulsive forces from the arms being directed partially to the pool bottom. The remainder of the body is streamlined to perfection. The legs and hips being elevated behind the torso produce less drag than if they had remained horizontal. A rapid adduction of the upper arms occurs producing a very large force.

- Frame #7: The head is raised as high as needed and the hands and forearms are realigned to produce propulsive forces backward. Rapid upper arm adduction has occurred. The knees start to bend preparatory to kicking.

- Frame #8: The hand/forearm-propelling surface is now aligned almost completely backward. Inhalation commences. The knees continue to bend readying to kick while the feet remain at the surface.

- Frame #9: The legs kick down to counter-balance the rapid backward and upward movement of the arms. At this stage the hands are still pressing backward even though the elbows and upper arms have exited the water.

- Frame #10: The kick is completed and the arms are fully extracted. A noteworthy feature of this frame is the straight but angled alignment of the body and legs.

- Frame #11: The body and thighs remain set at the same angle as in the previous frame. As the knees bend, only the lower legs move.

- Frame #12: The body and thighs still remain at the set angle while the lower legs continue to rise preparatory to kicking. The consistent thigh-body angle is notable. This means that Mary T.'s recovery is sweeping and flat, containing very little vertical component. If there were an "up-and-over" movement there would be some reactionary change under the water. This does not occur to any appreciable degree.

- Frame #13: As the arms start to stretch forward and over the surface the head is quickly lowered back into the water. The legs continue to rise and still the body-thigh angle remains constant. The length of time during which the body-thigh angle has been maintained means that energy has been conserved a feature that would be very helpful in 200 m races.

- Frame #14: The upper arms begin to break the water's surface as the entry commences. The kick is initiated by repositioning the feet. The head is completely covered. The hips are raised quickly as the shoulders are lowered and the body approaches a flat streamlined position. This frame occurs just prior to the position demonstrated in frame #1.

- Frame #15: A position very close to that illustrated in frame #2 is attained.

Mary T. Meagher's stroke can be described as being elegantly simple. It contains no exaggerated actions or positions, maximizes length of stroke, and exhibits features that do not exist in today's top women butterfliers. In a study that compared Mary T. Meagher, Susan O'Neill, and Petria Thomas, all swimming at training speed, the following were found:

- the range of movement of Mary T.'s feet, knees, hips, shoulders, and head were the least of the three;

- backward propulsion of her arms occurred earlier in the stroke than the other two;

- her kicks occurred later in the corresponding arm positions than the other two; and

- changes in acceleration of her center of gravity were much smoother and less extreme than the other two.

A striking feature of that study was that the range of angles achieved by Mary T.'s body, either after the entry (shoulders down, hips up) or during recovery (shoulders up, hips down), was less than either of the other two swimmers. In comparison, Mary T. Meagher moves more efficiently, with less exaggeration, and more smoothly. The narrower range of movements in each segment of the stroke alters the timing of the kick and the reaction of body parts.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.