HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

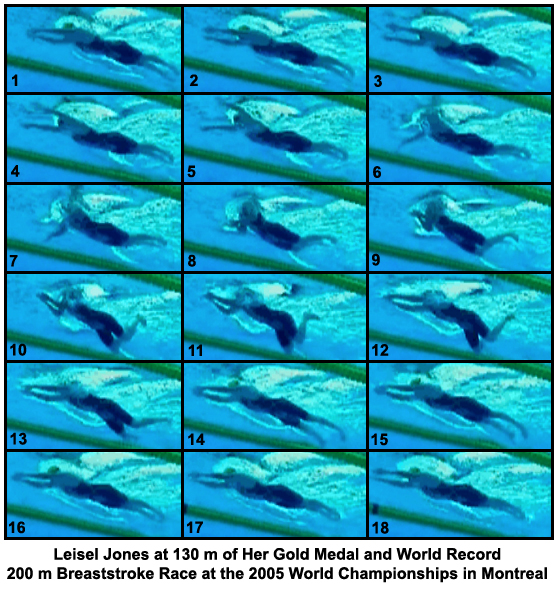

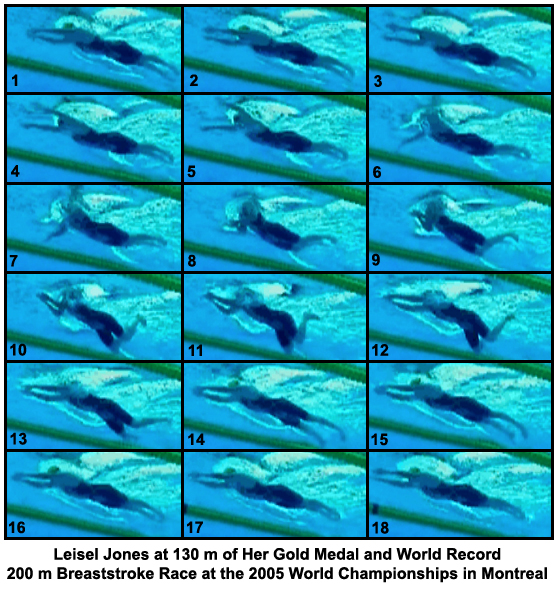

LEISEL JONES AT 130 m OF HER GOLD MEDAL AND WORLD RECORD BREASTSTROKE RACE AT THE 2005 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS IN MONTREAL

Each frame is 0.1 seconds apart. Leisel Jones' time for the event was 2:21.72, a new world record. This analysis is particularly important because Leisel Jones is improving more than other breaststrokers in the world are and she is distancing herself further from those swimmers in terms of absolute race time.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

Because other analyses of Leisel Jones on this web site demonstrate the intricacies of her stroke, this analysis will highlight only the major factors in this sequence.

- Leisel Jones' overall stroke is a fluid movement demonstrating barely noticeable changes in velocity from one stage to the next. This "smoothness" contrasts with other breaststrokers who display sudden changes in movement velocity, particularly in the arm stroke, which give the impression of a jerky action. In terms of energy expenditure, smooth actions that minimize velocity changes result in the most efficient use of energy. Smooth actions also minimize "cavitation". [When moving in fluids, sudden changes in movement velocity cause the fluid to "give" somewhat until appropriate within-fluid pressures are established. Thus, with every sudden movement, the potential length of a propulsive phase is shortened due to the distance "slipped" through this phenomenon, normally termed cavitation.] The lesson to be learned from Leisel Jones here is to stroke smoothly with the arms, gradually accelerating through the whole movement (not at just some stage in the arm cycle), and deliberately avoid any semblance of a jerky motion.

- A second feature of Leisel Jones' stroke is that which has emerged in other breaststrokers. Her kick is timed to start propelling backward when her body is almost flat after returning into the water from breathing and her arms are almost extended forward. By the time her kick is fully effective (see Frame #12 in the following analysis) the kick is propelling the swimmer when in a position of minimal frontal resistance. The lesson here is to maximize the effectiveness of the kick by aligning the arms and body/head in the most streamlined position possible.

- Leisel Jones' allows all the aspects of her stroke to be completed correctly. No action is forced or executed when another aspect of the stroke is ostensibly performing a productive action. Thus, she displays a classic two-phase stroke. The arm cycle and breathing action are completed before the propulsive phase of the kick is executed. However, the transition from one phase to the next is synchronized so that there is no period where nothing productive happens (the "inertial lag phenomenon"). The lesson from Leisel Jones? Do not rush the phases of breaststroke races that are 100 m or longer, and do not allow inertial lags between stroke phases.

- A final commentary on Leisel Jones' stroke is that she does not perform any unnecessary vertical movements. Unfortunately, in the early 1990's, the "wave" breaststroke became fashionable. It featured deliberate exaggerations of vertical movements, which make no sense from either a physics or hydrodynamics viewpoint. Some swimmers today persist with shooting the hands forward and over the water in the arm recovery. The energy cost of that untoward action would be significant in races longer than 50 m. It would also require some other part of the swimmer's action to go deeper in the water (probably the direction of the kick would be slightly downward rather than straight back), because the body would rotate about the center of buoyancy in a counterbalancing action. The lesson here is – do not deliberately create or exaggerate vertical movements in any part of the breaststroke action.

Leisel Jones is swimming remarkable breaststroke times and technique. Some features of her stroke, which are in accord with good fluid mechanics, could serve as models for emulation by other swimmers. This following collage would be a good teaching tool.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.