HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

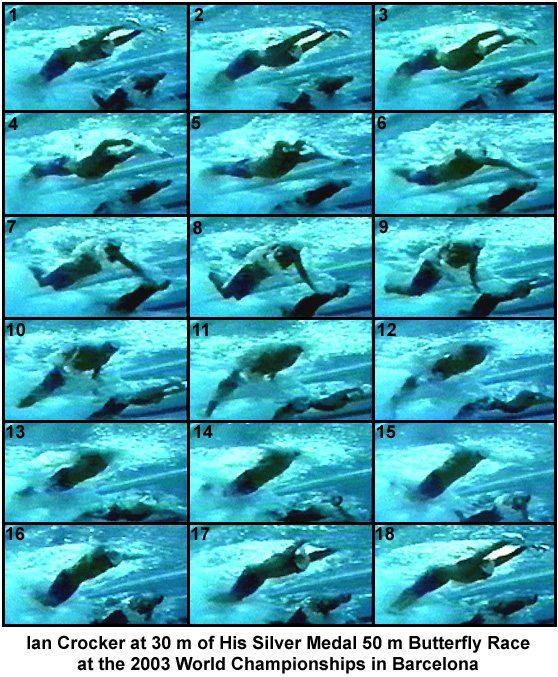

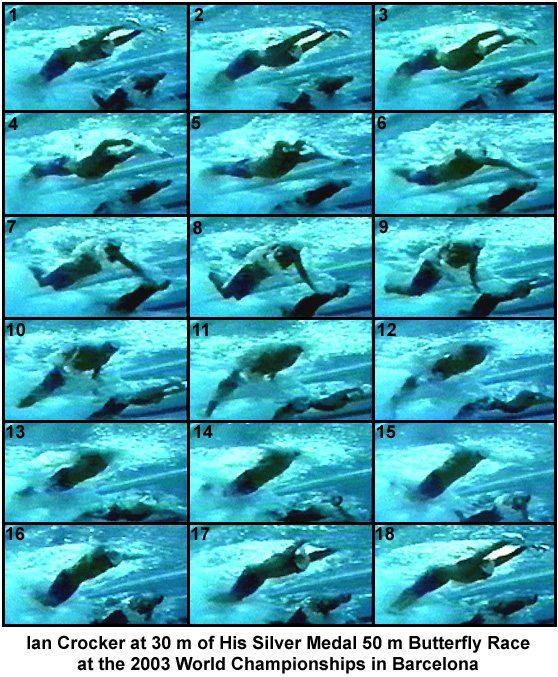

IAN CROCKER AT 30 m OF HIS SILVER MEDAL 50 M BUTTERFLY RACE AT THE 2003 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS IN BARCELONA

This clip is slower than normal speed. The length of time between each frame is not known. Ian Crocker's time for this silver-medal swim was 23.62.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

Frame #1: Entry is made with the hands facing downward about head-width apart. Being a sprint race, the vertical force component of the entry is quite high and requires a large counterbalancing kick to keep the body and head level.

Frame #2: The wrists are bent and a well-extended downward push is executed. The kick continues. It is excessively large and causes the hips to rise.

Frame #3: The arm action produces a strong vertical force component. Abduction of the upper arms and flexion of the elbows and wrists places the arms into an icnreasingly powerful position. The hips have continued to rise as a result of the kick. However, the chest and head have remained relatively stable because hyperextension of the lower back has accommodated the hip elevation.

Frame #4: Power produced by the arms continues to grow as abduction of the upper arms and flexion of the elbows increase. Some force is used to elevate the head and shoulders, which begins in this frame. The drag pocket of turbulence coming off the back of the arms and hands shows that the arms produce no forward propulsion at this stage. Force created by the kick has ended and so support for elevated hips no longer exists and they return to a more efficient streamline alignment with the torso.

Frame #5: Vertical arm forces continue to increase. However, for some reason, the hands evert briefly causing a reduction in power. The legs, hips, and torso are momentarily streamlined.

Frame #6: The hands flatten and begin a slight inward sweep. Arm forces still are primarily vertical. Upward movement of the head ceases.

Frame #7: Propulsive force powered by accelerated abduction of the upper arms is produced. The feet reposition to kick. The head starts to flex at the neck.

Frame #8: Arm propulsion continues to increase. Abduction has changed to adduction. Although a horizontal force component is developed, some vertical component continues to be produced requiring a counterbalancing downward kick.

Frame #9: A large propulsive force is developed on the surfaces of the hand, forearm, and upper arm of both arms. The impulse created by this movement may be brief but it is the strongest action in any form of swimming. The downward kick offsets the vertical force component of final arm adduction.

Frame #10: Arm propulsion is developed by extension at the elbow since adduction has ceased. Extension produces a vertical force component as the hand and forearm rotate upward. The kick is very deep.

Frame #11: Elbow extension continues as the hands "round-out" to initiate recovery. The head and shoulders begin to rise.

Frame #12: The head and shoulders rise as the arms elevate in recovery.

Frames #13 through #15: Recovery occurs. The hips drop slightly as the knees bend preparatory to kicking to counterbalance the eventual entry. The head returns after a very brief breathing action.

Frame #16: The head is returned as the arms approach the water.

Frames #17 and #18: Kicking occurs to counterbalance the entry of the arms. The stroke cycle begins again.

The kicking action that produces elevated hips is similar to that of Michael Phelps. Normally, this would not occur because it is unnatural and disrupts beneficial style features such as streamline and absolute counterbalancing. It is most likely due to the swimmer trying to get the hips up to produce an exaggerated undulating body movement, an aspect of butterfly swimming that is coached in belief that large hip undulations are desirable. Some hip undulation should occur in butterfly stroke but it should only be of a magnitude that accommodates efficient kicking and swimming economy. Exaggerated hip undulation is tiring and reduces propulsive efficiency.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.