HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

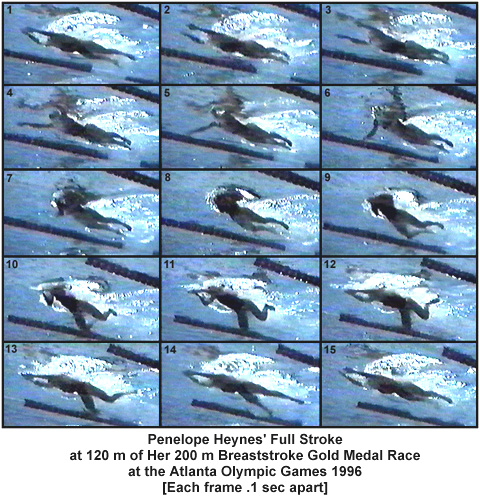

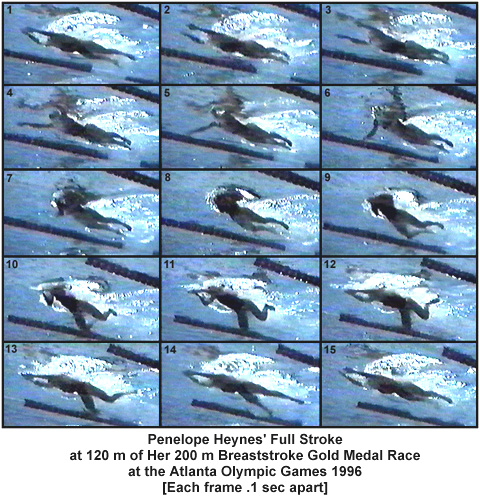

PENELOPE HEYNES' FULL STROKE AT 120 m OF HER 200 m BREASTSTROKE GOLD MEDAL RACE AT THE ATLANTA OLYMPIC GAMES 1996

Each frame is .1 second part.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The propulsive phase of the kick is completed and the feet are being drawn together to the surface to produce a streamlined position. The arms, head, shoulders, and hips are all aligned and horizontal producing a very flat and long posture. The head is down between the arms and looking toward the bottom.

- Frame #2: The arms start an outward scull before the feet are fully together. This action occurs while the swimmer is fully streamlined. There is very little time between the end of kick propulsion and the commencement of arm propulsion. Achieving continuous propulsion is a desirable quality.

- Frame #3: The hands scull out and slightly upward. The outward scull is almost completed. The elbows begin to bend as the hands continue to sweep while beginning a rounded path to conserve momentum in the arms. The downward (vertical) force component of this movement supports the initial raising of the head.

- Frame #4: The hands build the vertical force component that supports the start of an upward movement of the shoulders as well as the head. The hips and legs remain in a very streamlined position.

- Frame #5: The start of the inward scull at the end of the rounding action occurs through the adduction of the upper arm. This movement is different to that of Mike Barrowman as he kept his elbows wide and produced an "elbows-up" position. The head and shoulders continue to rise while the hips and legs remain streamlined.

- Frame #6: The position of the forearms and hands show clearly that much force is being created downward so that the head and shoulders can rise. The hips and legs remain streamlined.

- Frame #7: There is an acute bend in the middle of the back to enable the head and shoulders to rise well clear of the water while the remainder of the body and legs continue in a flat streamlined position. The knees start to spread apart as the first movement associated with drawing up the legs to prepare to kick.

- Frame #8: The arms are drawn in close to the body and complete producing vertical forces to support the head and shoulders out of the water. The legs are being drawn up to kick by spreading and bending at the knees. Optimum streamlining can no longer be maintained as the knees begin to be lowered as a consequence of hip flexion.

- Frame #9: The speed of drawing up the legs increases. The hands and arms begin to be thrust forward along the water surface. The head and shoulders start to return into the water.

- Frame #10: The head and shoulders are driven down and forward as fast as possible while the hands and arms are also driven forward. The velocity of this movement is accelerating. The legs continue to be drawn up while the feet are dorsi flexed to prepare to kick.

- Frame #11: The legs are decelerating as a consequence of the need to change direction to effect a kick. The feet begin to turn out even though the legs will still compress more. The face and front of the shoulders have entered the water and start to attain a streamlined position.

- Frame #12: The head and shoulders are now down and flat in line with the hips. The downward force of the returning head and shoulders is likely, as a reaction, to cause the hips to rise, further aiding streamlining and the production of a kick that is backward rather than down and backward. The kick is started with the feet fully rotated so that a full propulsive surface comprising the inside of the feet, ankles, and lower leg (shank) is produced.

- Frame #13: A wide sweeping kick is achieved parallel to the surface with the arms, head, and upper body in a very streamlined position. This position is very similar to that of Mike Barrowman at the same stage of the stroke.

- Frame #14: The legs are almost fully extended and wide. The streamline of the total arm, body, and leg alignment is clear. The leg width at this stage is no cause for concern as the swimmer's legs have effected a wide sweeping kick and in this position are moving quite fast on the way to finishing in a closed position. It is possible that this wide kick has exploited the swimmer's flexibility and leg surface area producing a larger kicking force than would result if an unnatural narrow kick was taught (coached).

- Frame #15: Full streamline is attained and the outward scull is initiated.

One has to question the reason for Penelope Heynes holding her head and shoulders out of the water so long. There does not seem to be any need to exaggerate this action to the extent demonstrated. It consumes much energy and time, factors that if refined and minimized, could contribute to a faster turn-over and the production of a larger horizontal component of propulsive force with the arm action.

The streamlining and timing of the stroke is very similar to that of Mike Barrowman. The body, head, and arms are flat and fully elongated during the propulsive portion of the kick. The exceptional speed with which the head and shoulders are returned to a flat streamlined position after inhalation is sufficient to allow most of the kick to propel a stationary flat posture through the water.

The flexibility of Penelope Heynes appears to be similar to that of Mike Barrowman. When the shoulders and head are raised to breathe, the hips and thighs/legs stay up near the surface. They do not drop down as a reaction to the elevation. This indicates that the power to raise the head and body comes almost entirely from the inward sculling movements in the arm patterns.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.