HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

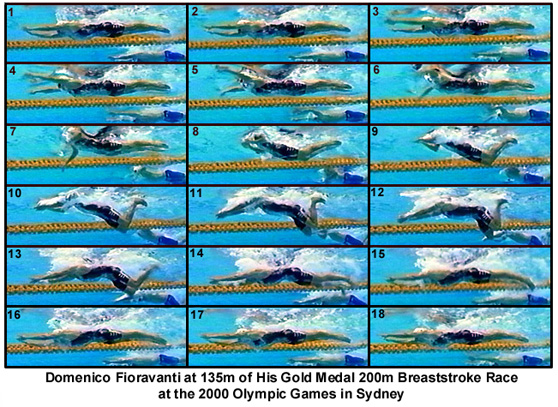

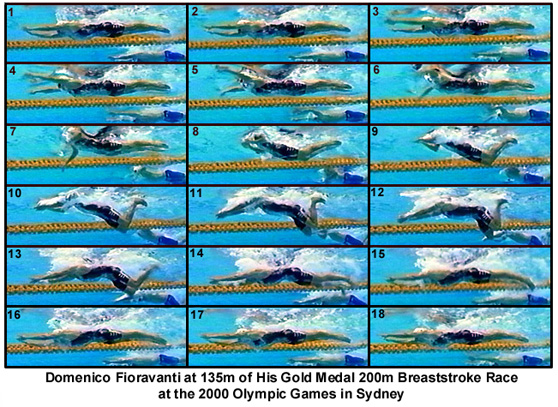

DOMENICO FIORAVANTI AT 135m OF HIS GOLD MEDAL 200m BREASTSTROKE RACE AT THE 2000 OLYMPIC GAMES IN SYDNEY

Each frame is .1 seconds apart. In this race, Domenico Fioravanti recorded a time of 2:10.87, the second fastest time in history. It was his second gold medal of the Olympic Games, as he also won the 100m breaststroke event.

Fioravanti is one of the tallest breaststrokers competing today. His height causes him to rate slower than shorter individuals because it takes longer for him to complete a full movement sequence.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

Frame #1: The stroking sequence commences with the torso, hips, and legs in perfect streamline.

Frame #2: Streamline is maintained as the hands begin to part.

Frame #3: The hands are angled outward to about 45 degrees. Their first forces will have vertical and horizontal components.

Frame #4: The vertical force component of the arm action begins to show in this frame. The head and shoulders commence to lift. The remainder of the swimmer continues in excellent streamline.

Frame #5: The arms have reached an acceptable width where elbow bending and adduction of the upper arms can commence. The rest of the swimmer is still streamlined.

Frame #6: The arm pull positions are very similar to those of a good butterfly pull. The forearms are angled, rather than vertical, so that an exaggerated torso and head lift can be achieved. A brief but powerful thrust is created. A major criticism of Fioravanti's stroke is his head and shoulders lift too high out of the water, which result in later stroke compromises. The lifting movements are achieved by hyperextending the back, which allows the hips and legs to trail in a streamlined position.

Frame #7: Adduction of the upper arms is nearly complete. The hand/forearm propelling surfaces have continued to produce vertical and horizontal force components that contribute to forward propulsion and support the high head/shoulders breathing action. The hips begin to drop as supportive vertical propulsion from the arms ends.

Frame #8: Inhalation is complete, the hands have come together very quickly, and the knees begin to bend to keep the feet near the surface (in readiness for drawing the legs to the buttocks preparatory to kicking). It is worth noting that in this type of breaststroke pull, where forces are created backward through the development of drag resistance on the back of the hand/forearm surfaces, there is no inward scull that produces a lift force. The hips continue to drop lower in the water as a reaction to the feet and head and upper body positions and movements.

Frame #9: The arms begin to thrust forward. Drag resistance created by the upper surfaces of the arms is clearly shown as the "white water" turbulence trailing them. The head and shoulders begin to return after inhalation. The legs continue to draw up with the feet already being positioned for kicking.

Frame #10: The arms thrust forward and down. The downward movement is a consequence of the excessive head and should lift. The downward movement serves to halt the returning head and shoulders from diving deep. The legs continue to be drawn up. As the knees go down, the hips flex, and along with the diving shoulders, the hips react by elevating.

Frame #11: As the head and shoulders plunge downward, the arms drive down creating a drag force on their upper surface. That force can be seen by the large and obvious turbulence following the arms. That force restricts the depth of descent of the head and shoulders. At the same time, the hips rise as rotation occurs around the center of buoyancy. The legs continue to compact preparatory to kicking with the feet staying near the surface. The knees are comfortably apart.

Frame #12: The positioning and slowing of the head and shoulders dive continue. The body is close to streamline. The kick commences with the feet fully turned outward.

Frame #13: Propulsion from the kick drives the remainder of the swimmer forward. The kick is directly backward. Hydrostatic forces created by the propulsion now support the head, shoulders, and torso. Consequently, the arms cease diving and begin to be realigned to streamline. Opening the underside of the hands to the oncoming water causes the arms to rise.

Frame #14: By the time the kick has completed its propulsion (there is no propulsion once the legs have slowed and the feet start to sweep together), the swimmer is streamlined again. The leg kick does not end when the legs are straight, as that would eventually injure the knees. The kick ends when its full directness is achieved. The coming-together of the feet and legs is purely a streamlining phenomenon.

Frame #15: The feet are almost together and streamline is almost perfect.

Frame #16: This is a position of perfect streamline. The hands/arms are now completely aligned with the rest of the swimmer.

Frames #17 and #18: The positions in frame #1 and #2 are attained again.

From a cursory glance, adherents of "wave breaststroke" would claim that Domenico Fioravanti swims with a wave motion, and derives some "mystical" benefit from that notion. However, it can be seen from this series that the diving and then ascending hand movements are purely reactionary or counterbalancing movements to a head and shoulder action that is excessively high. This is the typical reason why most "wave breaststrokes" swim with a wave action. It is a symptom of a fault, not evidence of a hydrodynamic benefit. If would be interesting to see what would happen if Fioravanti did not lift so high to breathe. For one thing, it would increase his rate, reduce the development of unnecessary drag resistance (such as that on the top of the arms), and would reduce wave resistance that results from unnecessary body movements. His head and shoulders lift and breathing action are mainly supported by hyperextension of the back, a feature becoming more noticeable in all top-breaststrokers of both genders.

The strength of Domenico Fioravanti's stroke comes from his adduction-powered, but short, arm thrust, and his powerful direct kick that uses every bit of his very long legs. This kick might well be the most powerful exhibited on this web site.

The superb streamlining displayed for most of the stroke could serve as an ideal depiction of one of the technical demands of this stroke. The length of time that the streamline is maintained is notable.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.