HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

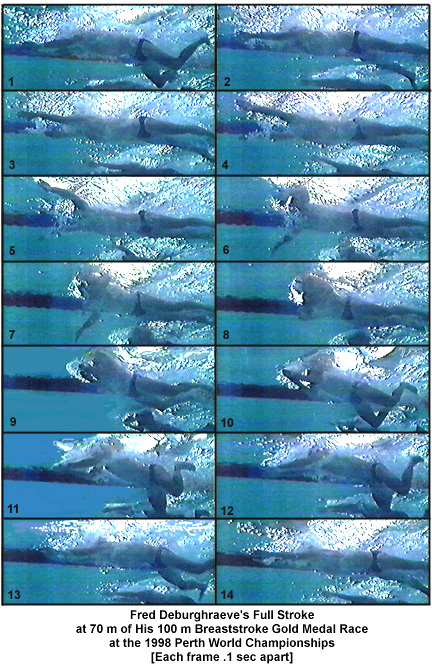

FRED DEBURGHRAEVE'S FULL STROKE AT 70 m OF HIS 100 m BREASTSTROKE GOLD MEDAL RACE AT THE 1998 PERTH WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS

Each frame is .1 second apart.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The legs are in the latter stages of the kick. The knees are well apart and the feet turned completely out and at right angles to the kick direction. The body and arms are flat and streamlined.

- Frame #2: The propulsive portion of the kick is completed. The legs are straight and the feet are being turned in for streamline purposes. The hands start the outward press (scull). This suggests that in sprint breaststroke, it is important to continually apply force. As soon as the legs complete propulsion, the arms should start. There is no glide in this movement sequence.

- Frame #3: The legs trail straight behind, but not together, with the toes pointed. The arms press out and slightly upward. The torso remains flat. The head begins to rise.

- Frame #4: The horizontal alignment of the torso and legs enhances streamlining. The head continues to rise. The arm pull continues to press out and upward. The palms of the hands begin to face backward.

- Frame #5: The arms are at their widest and begin to bend at the elbows to maintain momentum "around the turn." The hands predominantly face backward. The legs remain slightly apart but horizontally aligned with the body. The head has broken the surface and the face profile is vertical.

- Frame #6: The arm sweep around the turn is vigorous. Adduction of the upper arms and flexion at the elbows produce a very fast hand movement. The hands are repositioned for inward sculling. The head continues to rise while the body and legs still remain quite flat.

- Frame #7: The upper arms are drawn back past the shoulders. The upper arms, forearms, and hands create considerable force in the vertical plane to support the rising upper torso and head. The hips and legs remain long but begin to drop as a reaction to the vertical movement of the torso and head.

- Frame #8: The hands are brought up under the chin and the elbows are drawn to the side of the body in a very vigorous movement. The head is at its highest out of the water and inhalation occurs. Although the body-legs angle has increased the alignment is still long however, a slight bending of the knees reduces the frontal area of the total legs. Bending of the knees initiates drawing the legs up to the buttocks preparatory to kicking.

- Frame #9: Inhalation is completed and the hands/arms recovery forward commences. The legs continue to bend preparatory to kicking.

- Frame #10: The hands/arms recovery forward continues under the water. There is no attempt to recover over the surface, a movement that would force further inclination of the torso and thighs resulting in increased resistance. Recovering under water keeps the frontal resistance created by the torso and legs to a minimum. The speed of the leg draw increases and the ankles are dorsi-flexed ready for kicking. This early ankle flexion facilitates the feet being ready to propel from the very beginning of the kick backward. The head begins to be lowered.

- Frame #11: The hands/arms are thrust forward and down and are accompanied by a very quick head movement. The time to return the head to the water was .3 of a second whereas it took .6 of a second to rise and inhale. The knees and hips are flexed and the feet are being turned out.

- Frame #12: The hands/arms continue to be thrust forward but do not go any deeper than in the previous frame. A driving and downward action of the head and shoulders alters the angle of the torso to being flatter than in the previous four frames. In this swimmer's stroke, the torso is not streamlined for less than .4 of a second in a stroke that lasts 1.2 seconds. The kick commences. The positioning of the knees allows the feet to be fully everted so that a maximum surface area (inside of the foot, inner ankle, and lower leg) is presented as the propulsive surface to drive backward and create the largest drag force possible. Typical of most great breaststrokers of both genders, Deburghraeve's kick is initiated with the feet already turned outward. No part of the kick is lost with the feet in a less than fully everted position.

- Frame #13: The head and torso approach full streamlining. This position is similar to that depicted in frame #1.

- Frame #14: This position is similar to that in frame #2.

Fred Deburghraeve is a sprint breaststroker. His stroke is one that maximizes streamlining, minimizes the time spent in non-streamlined positions, and employs a fully effective kick. Also, the only lag in propulsion occurs during the leg draw, breathing, completion of the inward scull, and initiation of the hands/arms recovery. His is a stroke that has all those movements that disrupt streamline occur at the same time.

No unnecessary movements or movement paths are demonstrated.

Fred Deburghraeve's stroke is one that suggests the primary role of the inward scull is not necessarily that of propulsion but one of providing force to elevate the shoulders and head for inhalation. That force minimizes a "rocker" reaction of the hips and knees. The benefits of that streamlining effect are perhaps more than has been considered by most "stroke specialists."

Return to Table of Contents for this section.