HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

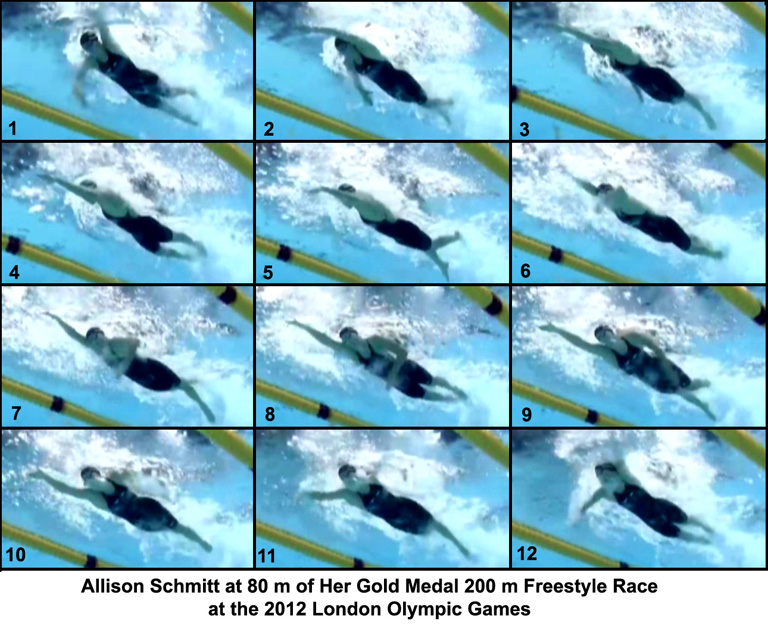

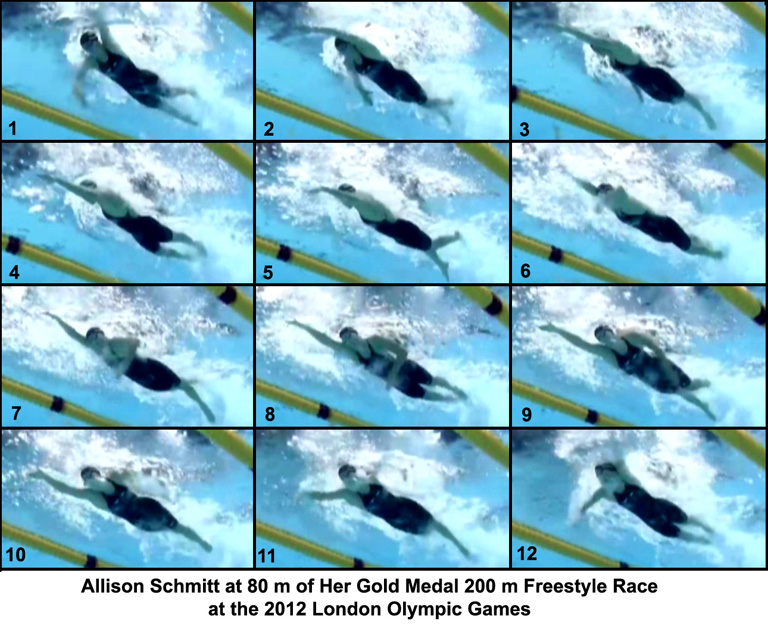

ALLISON SCHMITT AT 80 m OF HER GOLD MEDAL 200 m FREESTYLE RACE AT THE 2012 LONDON OLYMPIC GAMES

Allison Schmitt won the 200 m freestyle race at the 2012 London Olympic Games in very impressive fashion. Her time for the event was 1:53.61. In this analysis the frames are 12/100ths apart.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

There are two reasons for analyzing Allison Schmitt's splendid 2012 Olympic Gold Medal race. First, to see if there are any outstanding or novel features about her arm stroke and second, to look at her kick since she is reputed to be a serious kicker in her crawl stroke action.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The left arm enters bent while the right arm is just past mid-pull. Streamline looks good. The left foot is high indicating that the kick on that leg is about to occur. The timing of left-arm entry and left-leg kick occurring simultaneously is unusual because it is generally accepted that a kick counterbalances the entry or exit of the opposite arm. The right leg has finished vertical force production and the foot is streamlined. However, the right-foot's trailing turbulent water indicates that at that moment the right leg is creating a force that is against the swimmer's forward movement.

- Frame #2: The left arm stretches forward under the water increasing resistance, evidenced by the milky low-pressure water on the top of the arm, and possibly counterbalancing some of the vertical force component that has entered into the latter portion of right-arm pull and even that created by the left-leg kick. The right-arm is beginning to diminish in its propulsive force production. The left leg has also begun its vertical-force production while the right foot changes to a non-streamlined position before being raised to kick.

- Frame #3: The right arm has finished propulsion and is beginning its exit action. The left shoulder extends forward as the swimmer rotates to lower the left shoulder. The left leg has completed its kick. Its final position creates drag and is far from streamlined.

- Frame #4: The left arm extends fully forward and is "cocked" ready to initiate a propulsive segment of the stroke. The right leg kicks to counterbalance the vertical force beginning to be created by the left arm. The left leg is slightly obscured by a small but noticeable amount of turbulence on its underside. That phenomenon is explained by the unnecessary feature of "hard" kicking swimmers. The ferocity of the down-kick of one leg is of such magnitude in terms of vertical force production that the other leg has to be raised with effort to create a partial counterbalancing vertical force. The remaining counterbalancing force is produced by an arm. That is unproductive because energy is being expended to cancel forces that are not propulsive. Unfortunately, too many coaches "believe" kicking in free-swimming, as opposed to when using a kick-board, is propulsive. In truth, the legs and feet in crawl stroke swimming never achieve positions where a propulsive force of any value might be created. Consequently, when kicking hard, the excess downward forces of one leg have to be counterbalanced by a deliberate effort when raising the other leg. As is shown by this swimmer, the kicking action is only partly complimentary to the arm actions.

- Frame #5: The left arm begins its propulsive positioning. As has been shown with other swimmers such as Rebecca Adlington, Grant Hackett, etc., the first segment of propulsion is the repositioning of the forearm and hand to produce the largest propulsive surface possible that is at a right angle to the intended direction of movement. Here the wrist flexes to a small degree while the elbow begins to flex, the upper arm medially rotates, and the lower angle of the scapula outwardly rotates. That will result in the upper arm being maintained high and forward. The right arm is recovering quickly. The right leg completes its kick and finishes in a position that creates negative drag. The left leg rises preparatory to kicking. The distance between the finished right leg and the raised left leg is much too great for efficient small and fast kicking.

- Frame #6: In 12/100ths of a second, the repositioning of the forearm and hand has been completed, which is quite fast. From the extended forward position of the left upper arm to the completion of propulsion is the "effective stroke length" of the left arm. Unfortunately, the right arm has recovered long forward over the water and is about to enter. That causes the swimmer to rotate the shoulders to a flatter position. In turn, that causes the left arm propulsion to be alongside the swimmer which will cause a lateral force to be produced that has the potential to turn the swimmer away from a direct line down the lane. To counteract that turning force produced by the left arm, the left leg kicks and acts like a rudder to keep the direction of the overall movement down the pool. The right leg continues to rise preparatory to its next kick.

- Frame #7: The left arm is propelling. For the central portion of the propulsive phase, the work is done by the upper arm as well as the forearm and hand. This constitutes an example of "total arm propulsion" which is a characteristic of most, if not all, free style champions of today. The forearm and hand are fixed relative to the upper arm and remain vertical while the upper arm abducts and then adducts. The advantage of upper arm use is that the many muscles of the internal and external rotators of the shoulder are employed fully. In another position their force-producing qualities would be diminished greatly. The position displayed here is perhaps the strongest position of the propulsive phase. The right arm has entered and is extended forward. This is a classic picture of the undesirable overtaking ("catch-up") stroke. A small vertical force component is created by the right arm to prevent any more roll while the left arm is in its most powerful stage. Of particular note is the depth and position of the rudder-acting left leg. The negative forces (negative relative to propulsion) are quite large and necessary. The deep leg-drag would not be required if the swimmer was swimming over the pulling arm rather than being alongside it. The force of the left-leg kick has been such that the left hip has rotated upward. The line of the hips and shoulders are in different directions which is a definite flaw because it increases the frontal resistance of the total swimmer.

- Frame #8: The left arm continues propulsion. The upper arm has adducted almost completely into the swimmer's side. As the upper arm drops out of the propelling-surface equation the forearm and hand have continued to apply force backward by being close to a right-angle to the direction of travel. That is an excellent feature. The right leg kicks in preparation for the left arm exit and its incumbent vertical force component. The right arm continues to be extended forward. The face has rotated forward somewhat when compared to its position in Frames #1 and #2. The left leg rises forcefully. Once again the definition of the leg is partly obscured by the drag resistance on the shin and foot. It should be clear that "hard" kicking requires force to be created on the downward and upward leg movements while no valuable effect is produced for progressing forward. If anything, hard kicking produces substantial negative drag resistance.

- Frame #9: The left arm begins its exit. The right leg kicks to counterbalance the vertical force component developed at the left arm exit. The position of the right foot is not streamlined and would "drag" on the swimmer's forward progress. The right arm presses down which triggers the left leg to kick to counterbalance the vertical for component. The head continues to look forward causing a small amount of turbulence to come off the chin. That turbulence indicates that drag resistance has increased because of the orientation of the face. The right leg has risen to such an extent that the foot is above the water surface (aka. "kicking air").

- Frame #10: Because of the angle from which this video was taken, the true representation of the swimmer's right-arm propulsion is obscured. In another part of this race in a video that is taken from the swimmer's right side, similar dynamics to the left arm are evident. The right arm presses down as flexion at the elbow commences. The left-leg kick is almost completed counterbalancing some of the forces created by the right arm. The face looks further forward and a "beard" of turbulence appears to be streaming from ear to ear below the nose. That elevated head position creates a rotational force that causes the lower part of the body and legs to sink, which would reduce streamline. To prevent sinking either or both of two actions have to happen; i) the forward arm presses downward so that the added force supports the rising head, and/or ii) the kick has to be more vigorous and possibly deeper than usual to "kick" the back end of the swimmer toward the surface to maintain streamline. The right leg has risen.

- Frame #11: The right arm begins to pull noticeably. The upper arm has begun to abduct before the forearm and hand are at right angles to the direction of propulsion. The left arm is at the highest point of its recovery. The left leg is very deep producing considerable drag resistance. The turbulence off the forward-looking face has grown and is very obvious.

- Frame #12: The position in this frame is one step before replicating what is shown in Frame #1. The right arm is in a good position showing its three segments constituting the propelling surface. Unfortunately it is to the side of the swimmer rather than underneath. The left arm recovers forward. The right leg begins to kick possibly to accommodate the early entry of the left arm (see Frame #1). The drag resistance off the face is clearly evident. Perhaps this is part of the swimmer's breathing action. Instead of simply rotating the head on the horizontal axis to breathe, she first lifts the face and head forward and then turns to breathe. That is a cumbersome resistance-developing action and could easily be corrected by adopting a simple rotation to the side to time inhalation with the end of force production of the arm on that side. That is likely to be true for this swimmer because the head has begun to turn to the right.

Several obvious changes that could be made to improve this swimmer exist.

The recovery of both arms should be over the water rather than spearing in early (Frame #1) and then reaching forward underwater. Not only does this increase drag resistance for the total swimmer but it also prevents what could be a formidable shoulder action. With the arm entering and extending forward, the shoulder of that arm also has to be underwater causing the shoulders to be quite flat. With an over-the-water recovery, the shoulder remains elevated out of the water causing the pulling shoulder to be deep which in turn facilitates developing propulsion under the swimmer as opposed to being out to the side as in this swimmer with its troublesome rotational effect.

Not only does the recovery need to be fully above the water but it has to be timed with the propulsive action of the other arm. That would remove any semblance of an overtaking stroke pattern and might even facilitate opposition or superposition timing. Although this swimmer exhibits a minor overtaking stroke timing, that still is enough to accumulate to precious seconds that are added to the swimmer's time for this event.

The swimmer's stroke is dominated by a big and furious kick. Since kicking in free swimming does not propel the swimmer, that exaggeration fatigues the swimmer unnecessarily. It also causes the stroke rate to be limited to the length of time it takes to complete six big kicks. Smaller kicks would not require as much time for six to be completed and thus, the swimmer could rate higher. As well, the forces that can be created by small fast kicks are quite small and would not consume as much energy as kicks the size of those exhibited by Allison Schmitt. What should actually happen is that any kicks should occur to counterbalance vertical forces created by the arms. As Forbes Carlile (personal communication) has so eloquently stated, "the legs should dance attendant on the arms".

Those two items are major. However, when considering technique changes in a senior swimmer, the decision to do so should be made against the possibility of a change being able to replace an established error. If a swimmer has been committing an error for many years, the probability of substituting a new action is very low because a huge number of repetitions of the new element would have to be exercised through the three stages of motor learning. Most coaches do not have the skill to teach such changes, and in particular have little appreciation of the techniques that need to be used to have the swimmer cognitively control the change at the outset and for a very long time. An occasional coaching remark to make the change will not effect a behavior change. Thus, there is a time in a swimmer's career where the error has existed for such a long time that the time and effort to produce a change is insurmountable and the error has to be tolerated.

Watching Allison Schmitt swim this 200 m race in London only engendered admiration for the way she established herself as the dominant swimmer in the race as well as the way she developed a large lead by the second 100 m. It seemed that the other competitors had conceded the race to Allison and they were to fight it out to see who would be the silver medalist (the "first loser").

Return to Table of Contents for this section.

![]()

![]()