HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

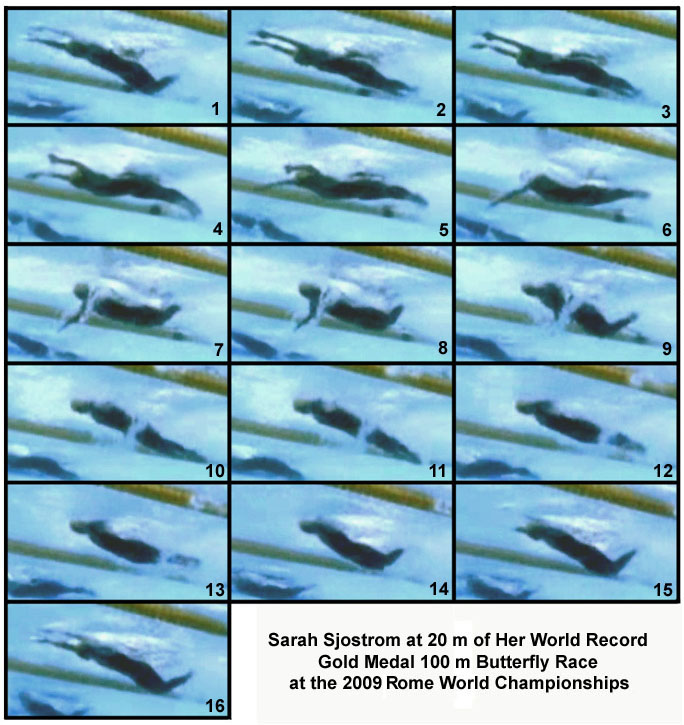

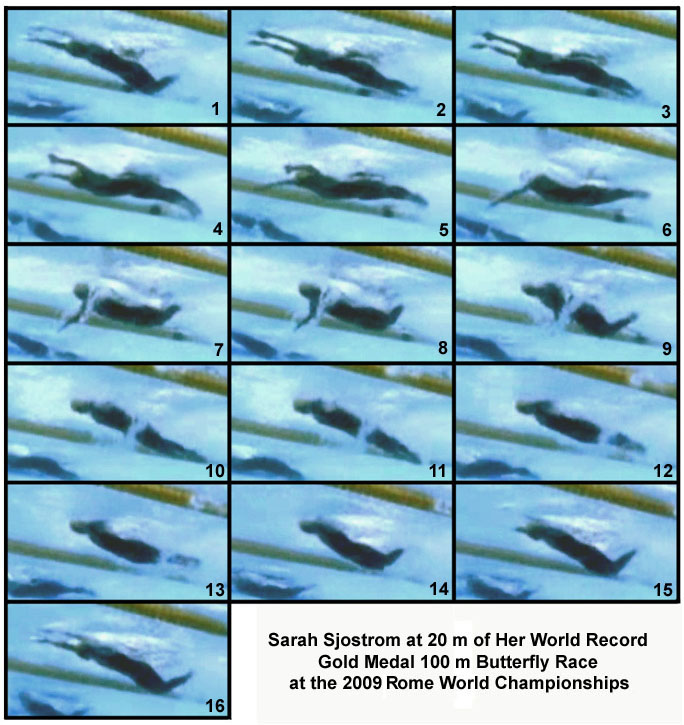

SARAH SJOSTROM AT 20 m OF HER WORLD RECORD GOLD MEDAL 100 m BUTTERFLY RACE AT THE 2009 ROME WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS

Each frame is .08 seconds apart. Sarah Sjostrom recorded a time of 56.06, a new world record for the event. At this stage of the race, other swimmers are ahead of Sarah, particularly Jessica Schipper who eventually placed second, also swimming under the old world record. It was only in the last 15 m that Sarah Sjostrom swam "over the top" of Jessica Schipper to record the win. It is inferred that Sarah Sjostrom's technique displayed here is one that accompanies her well-planned appropriately paced race. It is a non-breathing stroke.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

- Frames #1 through #3: As the entry is made the legs kick to counterbalance the vertical forces created by the arms. The arms are stretched fully forward and almost shoulder width apart. For a brief time (Frame #2) the swimmer is very flat. In Frame #3 the hands are angled outwards.

- Frame #4: The kick is completed. The hands have moved sideways as the elbows bend and the upper arms abduct. The torso is lowered through hyperextension of the spine. [The time taken to get into a propulsive position is relatively short when compared to swimmers of some years ago.]

- Frame #5: The arms move down and back and surprisingly, the hands have not yet turned.

- Frame #6: In a very quick movement, the hands are turned to orient down and back. As well, they have slid in close together. Propulsion begins because a drag pocket is developing along the total left arm (the only one visible from this perspective). The legs begin to rise.

- Frame #7: Both arms have fully abducted and generate a great amount of force, judged by the extent of the drag-pocket turbulence extending along the full arms. The legs continue to rise.

- Frame #8: The arms have moved only to a minor degree from the position in the previous frame. That suggests that the massive double-arm pull has "locked-onto" the water and the swimmer is being propelled past them. It is contended that for this brief moment there is little slippage of the arms through the water. The impressive arm action is powered by muscles involved in adduction. The legs continue to rise.

- Frame #9: As adduction of the upper arms is completed the legs kick to counterbalance the large vertical forces created by both arms beginning to recover at the same time.

- Frames #10 through #12: As the arms exit, the leg kick is completed. As the arms recover and proceed in front of the center of buoyancy (Frame #12), the swimmer begins to hyperextend the back causing the legs to rise.

- Frames #13 through #16: The recovery occurs with the legs being raised in readiness to kick on entry (Frame #16) when the stroke cycle commences again.

This stroke is most notable for what it does not do. Gone are the hands entering virtually touching, the hands then needing to be separated to the side for a wide distance, and the inertial lag that those unnecessary movements caused. The swimmer appears intent on reaching/swimming down the pool and producing propulsive forces quite rapidly after entering (thereby reducing the inertial lag).

Return to Table of Contents for this section.

![]()

![]()