HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

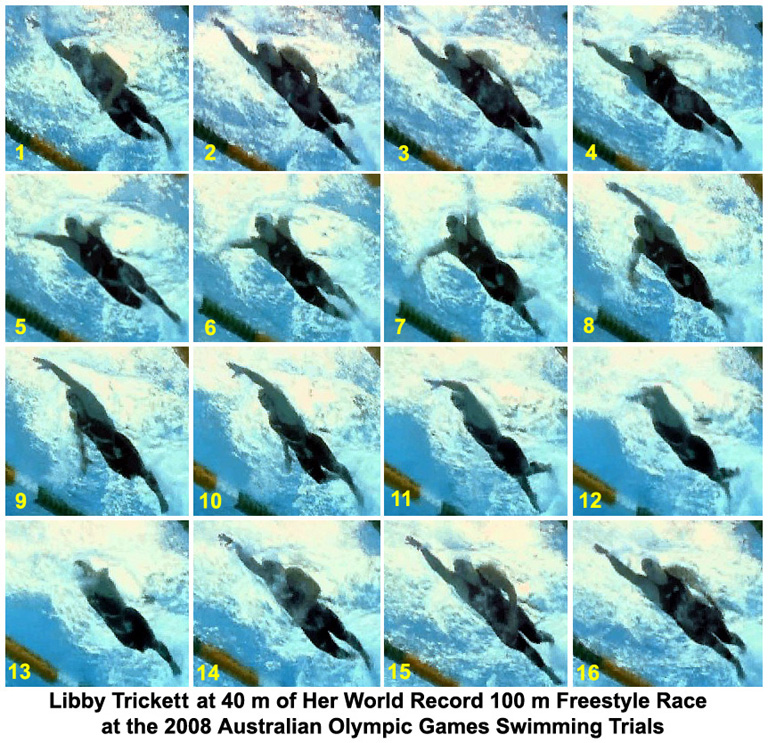

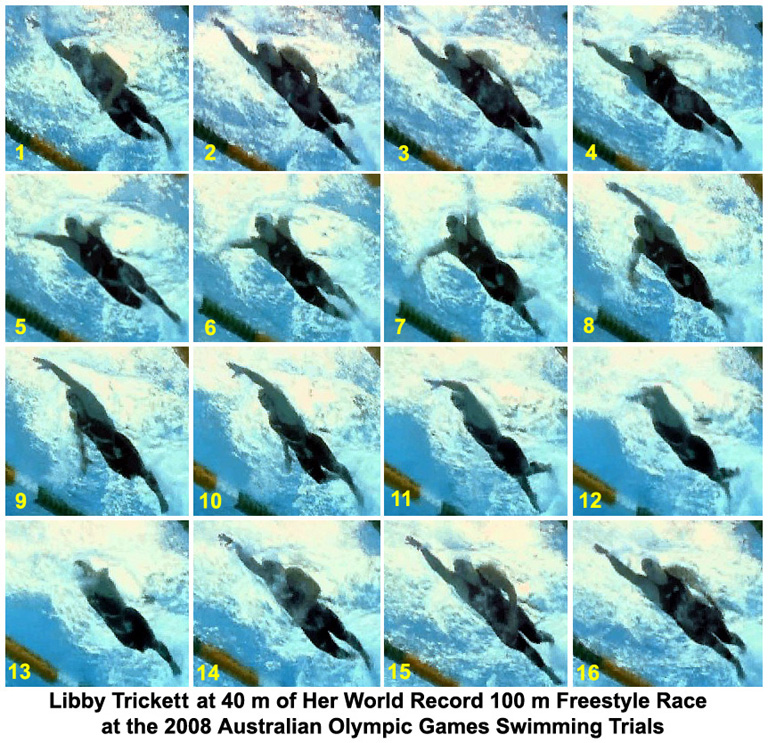

LIBBY TRICKETT (NEE LENTON) AT 40 m OF HER WORLD RECORD 100 m FREESTYLE RACE AT THE 2008 AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC GAMES TRIALS IN SYDNEY

Libby Trickett's time for this event was 52.88 seconds. The frames in this presentation were captured from a slow-motion replay of a section of the event.

This stroke analysis includes a continuous moving sequence, a sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in slow motion. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

Body Posture

The swimmer maintains excellent body posture throughout the stroking sequence.

- The swimmer's streamline (head-shoulders-hips alignment) is outstanding. It depicts a rigid posture along the horizontal axis, which results in minimal frontal resistance caused by the non-propulsive body sections.

- The hips and shoulders rotate along the horizontal axis. A conservative estimate is 30° rotation to either side. More rotation might consume time that would result in a diminished stroke rate. Less rotation would cause the power of the arm pulls to be diminished by producing an over-reliance on the internal rotation muscles of the shoulders. [Some swimming sages have opined that modern sprinters have flat stable hips (i.e., and absence of rotation). That impression is dispelled by the hip rotation displayed in Frames #4 and #11.]

- There is an absence of any lateral sway in the hips. Many reasons for stable hips of the form exhibited here have been offered. One is the bogus reasoning that superior "core strength" promotes the stability when in actuality the force required to hold a desirable posture in this fully-weight-supported sport is quite small. Another possibility is the swim suit used (a Speedo LZR) promotes the stability. That can be discounted because in the other clip of Libby Trickett/Lenton on this web site, similar stability is exhibited while she was wearing a non-stabilized suit. It is asserted that this controlled rigidity along the horizontal axis is a learned technique feature that is not reliant on any outside support mechanism.

- The amount of shoulder roll is sufficient to produce two outcomes. The first is that the upper arms are powered by both the internal and external rotators that produce impressive adduction and abduction. The second is that the combined appropriate elbow bend and outward rotation of the lower angle of the scapula coupled with medial rotation of the upper arm, situates the propulsive surface of the arm (which is centered about halfway up the forearm) so that propulsion is directly backward for most of the stroke (e.g., Frames #5 through #9 and #11 through #15).

Arm Actions

- The length of each stroke is about as long as possible. The arms extend fully forward underwater after entries that reach almost maximally over the water. The arms exit the water with the elbows only slightly bent. One should be careful and not assume that an added benefit would be gained by extending the arm fully at the stroke end (which would cause it to stop underwater and increase drag significantly).

- [The following is repeated from above.] The upper arms are powered by both the internal and external rotators that produce impressive adduction and abduction. The combined appropriate elbow bend and outward rotation of the lower angle of the scapula coupled with medial rotation of the upper arm, situates the propulsive surface of the arm (which is centered about halfway up the forearm) so that propulsion is directly backward for most of the stroke (e.g., Frames #5 through #9 and #11 through #15).

- The total arm produces propulsion in the major propulsive phase of each stroke. Propulsive effects in the form of drag forces can be seen by turbulence ("milky water" and not bubbles) that is in front of the arm. The angle of photography and the position of the major light source in this sequence show turbulence more clearly on the right arm (Frames #5 through #9) than on the left. Propulsion from the total arm in the major section of the arm pull when the dominant force component is direct and horizontal is one of the major technique changes that have occurred in crawl stroke over the past decade. The jettisoning of S-shaped pulls and the focus on what the hand does, both factors that have retarded the development of crawl stroke dynamics, and now focusing on the total arm can be postulated as a cause of crawl stroke improvements, particularly in sprint events, over the past few years.

- Because the length of the underwater stroke is so long and its load so high when compared to the recovering arm, it will consume more time than the recovering arm to complete its actions. The recovered arm will be "parked" forward until the appropriate time for it to start stroking occurs. There is no deliberate attempt to produce a "catch-up" or "overtaking" stroke (useless labels at best). The extra time forward after entry allows better positioning for a long stroke than if the hand was driven down after entry.

- Frame #10 shows an excellent change of force production. As the right arm completes its propulsive phase (its force production diminished in the latter stage of the pull), the left arm begins to be repositioned very quickly to produce the largest possible propulsive surface. This lack or minimization of inertial lag is of great mechanical advantage (it closer satisfies Newton's First Law) and ensures the swimmer does not slow noticeably during the arm-stroke change phase.

Breathing and Rate

- Modern crawl stroke swimmers rate very high. It is this writer's opinion that the "old" singular stress on stroke length, often to the detriment of rate, has ceased in many top sprinters. Now, sprinters rate so high that it would be uncomfortable and interfering to breathe every alternate stroke. Libby Trickett appears to have moved to a breathe-on-demand cadence. In her world-record 50 m swim at these trials, she breathed once. While long slower swimming at training facilitates rhythmical breathing, race-pace work should let the swimmer breathe on demand rather than forcing a too frequent rhythmical action. However, that does not reduce the need to teach swimmers to breathe properly (e.g., no head lift, turn on the longitudinal action, forcibly expel remaining air as the head is turned, breathe in the bow-wave trough, etc.).

- A major focus on training repetitions should be on the highest stroke rate possible while maintaining a maximal stroke length. That should result in swimmers achieving very high peak power in the stroke as well as "increasing the area under the force curve". In making that statement, one is reminded that great increases in propulsive power have to be achieved to improve race times because resistance also increases almost exponentially with increases in velocity. The corollary of that statement is that small technique changes that do not increase force appreciably will not produce notable performance changes in high level swimmers. Libby Trickett's arm stroke appears to be very powerful, involves a high rate, and is maximally effective.

Kick

- Libby Trickett's kicking action is not propulsive. The amount of turbulence that follows each foot is proof of no forward propulsion. It is fast and moderate (not exaggerated). It is sufficient to facilitate hip and shoulder rotation and to counterbalance the increased forces of the arms.

- The six-beat kick counterbalances the vertical forces of the entry and exits of both arms (four kicks) while the two kicks at mid-stroke facilitate the hips rolling which allows the final arm action to continue backward rather than having to move to the side to avoid the hips.

- It would be nonsense to attempt to get Libby Trickett to kick more in a race. Such an instruction would reduce the effectiveness of the arm pull.

Libby Trickett displays a very impressive crawl stroke which employs most of the recent developments in the stroke's physical principles as well as not perpetuating most of the erroneous coaching principles that have plagued the stroke over the past several decades.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.

![]()

![]()