2008 BODYSUITS - DÉJÀ VU?

Brent S. Rushall, Ph.D.,R.Psy.

San Diego State University

©Sports Science Associates

Spring Valley, California

Revised: July 6, 2008

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| SECTION | TITLE |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction |

| 2 | It Must Be the Bodysuit – or Is It? |

| |

| 3 | What Science? |

| 4 | Simple Science Can Be Valuable |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 5 | The Latest Speedo LZR Racer Bodysuit |

| 6 | Psychological Considerations |

| |

| |

| 7 | Further Considerations |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 8 | Closure |

| |

| |

| 9 | Footnotes |

| 10 | References |

The 2008 release of a new generation of swimsuits (bodysuits) by several manufacturers for competitive swimmers to use in Olympic Trials and Games has caused a stir of greater proportions than when the original bodysuits were released at the turn of the century. This part of the Swimming Science Journal relates what transpired with the pre-2008 bodysuits, and focuses most notably on Speedo products. Inferences are made about the 2008 bodysuits.

However, the current reactions of swimmers, the media, swimming officials, and individuals concerned about the bodysuits and the sport have led to an unheralded spate of coverage, perpetuation of propaganda, and pronouncement of beliefs not based in facts. Understanding what is happening and has happened with regard to bodysuits, and in particular the actions of Speedo, should place the current phenomenon in perspective.

It is popularly believed that the latest (and previous) bodysuits are performance enhancing. Wearing a bodysuit, such as Speedo's LZR Racer, is believed to cause swimmers to record faster times than they would if they were not wearing it. Where matters of cause and effect are concerned, the type of evidence referenced must be published in a refereed (scientific) journal and have been subjected to a number of experimental controls. Testimonies from experts or satisfied users do not qualify as evidence of effect.

It is recognized that much of what is contained in this article is contrary to the cleverly contrived dogma of the bodysuit manufacturers. Many will find this paper's assessments and conclusions dissonant with their own thinking. However, when one considers the popularity of the topic of elite swimming performances, the frequency of publication of the dogma surrounding the topic of bodysuits principally by an undiscerning media, and the mass hysterical acceptance of unfounded tenets that are expressed and presented almost on a daily basis about the equipment, the dissonance should be understandable. The shaping of public opinion, mostly through clever uses of propaganda and marketing, can get an unknowing audience to accept almost any "belief" – and often the belief that the "belief" is fact. Consequently, this article is evidence-based and its implications will clash with beliefs not based on proof. This discussion provides reasons for asserting statements as opposed to assumptions or speculations about the real world of swimming and swimming apparel. Hopefully, facts will win out and readers' opinions will change because of the knowledge base that is referenced and serves as the foundation for the arguments presented here.

2. It Must Be the Bodysuit – or Is It?

"And so it’s proved. In the two months after the Beijing suit – or LZR Racer – was launched in February, swimmers wearing it broke an astonishing 37 world records" (Parnell, 2008).

Barely a day passes when some journalist or on-line site does not extol the exceptional and superior qualities of Speedo's LZR Racer bodysuit. It has been hailed as a technological breakthrough. The superlatives have been so great, the qualities and attributes so causally miraculous for swimmers, and the claims so impressive that one is left with the impression that if the suit was thrown into a pool it would break a swimming world record on its own. Swimmers, their training, and their coaching have all taken a back seat to this accepted and sought after device.

Could there be other reasons for this unusual coverage? At least some possible factors should be considered.

The Marketing. This writer acknowledges without question the most excellent marketing strategy and its implementation for the LZR Racer bodysuit. As will be explained below, Speedo has promulgated dogma as propaganda in an overwhelmingly effective and impressive manner. Other manufacturers have been caught off guard by the intensity and success of Speedo's marketing plan.

It is well known in social psychology circles that beliefs will be accepted as facts if they have the following characteristics.

It would be helpful to analyze these factors and see if they apply to Speedo's marketing of the LZR Racer.

Who, Why, and What "They Say". Since 2000, Speedo has been increasing the number of major national swimming teams and world #1 ranked swimmers to be members of its stable of sponsored athletes. The contractual arrangements with those teams and swimmers are not known but it is obvious they contain obligations to promote Speedo products and to only speak well of them (i.e., represent Speedo with the best image possible). While at the 2000 Olympic Games a majority of Gold medalists did not wear full bodysuits (see a previous article on bodysuits in this journal), since then more champions and successful athletes have been obligated to wear Speedo equipment in their races. It is now generally accepted that the majority of world #1 ranked swimmers (and most are those who break world records) are Speedo representatives.

When the majority of world record breakers are required to wear Speedo equipment, it is not surprising that most of the new world records are produced by swimmers wearing a Speedo suit. Unlike the supposed development of the LZR Racer, understanding this contrived situation is not "rocket science" [pun intended as it relates to Speedo's publicized association with NASA – see below]. The simple fact that if the large majority of world record setting swimmers are contracted to wear Speedo bodysuits, when they break world records they will be wearing a Speedo suit. This simple association, and it is nothing more than an association, appears to have evaded the less than impressive analytical qualities of the world's sports reporters and feature writers.

In the quote at the start of this section, the implication that the Speedo LZR Racer bodysuit caused world records is contained in the words "swimmers wearing it broke an astonishing 37 world records". What has escaped so many is that this statement results from the same phenomenon that gives rise to superstitions – a causal attribution to be imbued upon an event that is associated with an outcome. It is likely that the same swimmers would have broken world records, without the LZR Racer bodysuit. For example, Libby Trickett (she is mentioned and illustrated several times in this article) was the first female to break 53 seconds for 100 m freestyle last year at the Duel in the Pool meet in Sydney. That was achieved without a LZR Racer. After an added year of training and a competitive stage that had selection consequences of extreme importance, she improved on that swim by .11 seconds. That difference can be justified because of other factors and not because of the LZR Racer bodysuit she wore.

Contracted Speedo swimmers and coaches are required to represent Speedo products in a number of ways. It is not surprising that they all speak in glowing terms about the LZR Racer. If they did not, then it would be at considerable personal cost as well as probable social ostracism. Also, today's teenagers know nothing but bodysuits in high level competitive settings. Few, if any, will have raced with a "brief" suit and full-shaved body. Consequently, they have no frame of reference with which to judge today's bodysuits. They will uncritically assume that bodysuits are traditional and best for racing. Because of that experience limitation, they are not the ones whose opinions should be heeded.

Thus, many esteemed swimmers and coaches (and scientists) shamelessly endorse the LZR Racer. Their conduct as shills (spokespersons) for Speedo products only serves to alter the beliefs of potential customers while the truth and accuracy of their statements go unchallenged [this article will challenge many of the attributes claimed for the latest version of the Speedo bodysuit]. Speedo's development of an extremely successful stable of already successful swimmers gives rise to the superstition that the LZR Racer causes world records. An all-believing public willfully accepts the words of the top swimmers and coaches and follows their advocacies. Followership of this type is but one aspect of the herding instinct of social animals.

The degree to which Speedo has infiltrated national swim coaching ranks to spread its propaganda is more than most people realize. One nation's coaching magazine has a contractual arrangement to once a year produce a Speedo-authored article that is nothing more than a disguised infomercial imbedded among coach-useful articles. The timing of that insertion is up to Speedo. In that same organization, board members are paid representatives of Speedo and have the power to use, and they have used it, to censor criticisms of their sponsor. The outcome of this intrusion is that the coaching organization is unable to disseminate information that might be correctly critical of a swimsuit manufacturer, and in this instance it is Speedo.

The Unfortunate/ineffective/irresponsible Role of the Media. All forms of the media have been exploited deftly to promote Speedo's claims. The overwhelming majority of the media repeat and propagate facts and fictions concerning the LZR Racer. For example, Parnell (2008), in what is nothing more than an infomercial rather than a feature article in the Australian Magazine, stated:

Speedo’s new, perfectly legal, state-of-the-art swimsuit was definitely performance-enhancing, and that it really could make the difference between winning a gold medal and coming nowhere. And so it’s proved.

Outrageous claims and the re-writing of history (as Parnell did when referring to Olympic swimming since 1992 being influenced markedly by Speedo products as the causes of results) are not within the standard of responsible reporting or advertising. As is explained below, many of Speedo's claims should be objectively verified as well as reflect the factual truth about the qualities of its products. A pet peeve of this writer with the general swimsuit manufacturing genre is the claim that products are developed by scientists – an unfortunate word choice because the characteristics of science and its purveyors is that it should be publicly disclosed to be objective, observable, and measurable. That has not occurred with any bodysuit by any manufacturer. The main requirement for advertising is that it should fulfill the following:

Advertisers must make truthful claims and substantiate all objective claims. These rules of the road, of course, apply both to advertisers using traditional media and those who market their products and services on the Internet, telephone, e-mail, or through any other media (Federal Trade Commission, 2000).

The complicities that exist between swimsuit manufacturers and the media, ostensibly so that the media can get "a story out", have served to repeatedly and frequently restate claims that are beliefs not based on proof. Unfortunately, if an individual says/reads/thinks of a statement often enough, he/she will come to believe it. That is the basic procedure of propaganda systems that have led to unquestioned religious faiths, social movements (e.g., Nazism and Communism – as well as just about any political form), fads (e.g., snake oil as a cure-all), and sects (that function outside the laws of a country). And so it is with swimsuits, and in particular the LZR Racer. Almost without exception, peoples, national organizations, and individuals believe it to have powers/qualities that will cause a swimmer to swim faster than ever he/she has. And so, the repetition of how many world records have been set in the LZR Racer has given rise to a common but very questionable belief. That end result is an obvious failure of the media to effectively evaluate what it reports as fact. That failure is irresponsible.

Parnell's infomercial is a good example of the manipulation of the media by a corporation for fiduciary gain. It and many others before and after should be read questioningly. The main structural ingredients used are the unscientific ploys of:

"Scientists" are included within the realm of appeal-to-authority. Parnell allows persons he interviewed to be labeled scientists when they did not act in that capacity for Speedo. They simply were resource persons probably judged by Speedo to have desirable qualifications. The roles of resource persons and scientists differ markedly. A resource person is paid (hopefully) to do work, the results of which are the property of the sponsor (in this case Speedo). There is no public reporting, scrutiny, evaluation, or sharing of data in the work done. It is unfortunate that persons with research responsibilities in public institutions do not recognize this difference. However, it is yet another remarkable accomplishment of Speedo to be able to use the personnel and physical resources of publicly-funded institutions (i.e., Australian Institute of Sport, University of Otago). One should hope that Speedo paid for the services and facilities in those settings. But, the major point should not be lost here. Parnell cloaked his reporting with hyped attributions to lead the reader to believe that real science was done in the development of the LZR Racer.

The Parnell report, as happens with most reports about the LZR Racer, only relates good events. A reader cannot finish the article without forming the impression that the Speedo bodysuit is responsible for improved performances and in particular, the setting of world records. However, not all performances wearing this engineered "marvel" are improvements or records.

At the 2008 Telstra Grand Prix held in Canberra, Australia late in June, Libby Trickett (world-record holder for 100 m long course freestyle) on Saturday, June 25 broke the short-course world record for 100 m butterfly wearing a LZR Racer. That swim is included in the 37 world records reported by Sean Parnell. On Sunday June 26, wearing a LZR Racer bodysuit again, she was beaten into second place by Angie Bainbridge in her supreme event, the 100 m freestyle, albeit short-course. It would be wrong for one to attribute the world record to LZR Racer qualities and benefits without also taking responsibility for Libby Trickett's "failure" the day after and attributing the suit to that. Only reporting and associating with successes is dubious because it does not relate the complete picture of swimming performances associated with the LZR Racer bodysuit. Unfortunately, that distortion has been repeated many times producing in naïve readers the belief that the LZR is only associated with swimming successes. It is more accurate to believe that wearing a high-tech bodysuit in swimming races is just as likely to result in an average or below average performance as one that is an improvement for the individual swimmer.

The Competitors' Lament. In an obvious form of reverse psychology, when competing manufacturers complain about Speedo's "advantage" (e.g., Dillman, 2008), witnesses raise their convictions (beliefs) about the quality and utility of Speedo products. The added media attention to all confrontations and complaints further uses the frequency of attention principle to strengthen observers' beliefs. The effects of competitors' complaints and criticisms about Speedo's products catch the competitors "between a rock and a hard place".

There are options for competitors to offset the initial and continuing primacy of Speedo's position in the swimsuit business. They could sponsor comparative research in a truly scientific setting – and run the risk that their products will prove to be inferior or that one or more products have no effects. They could target a different segment of the swimming community. Since Speedo has effectively corralled the elite market, perhaps the elite age-group or master's markets might be easier to capture. The actual strategy to counteract Speedo is the province of marketing groups. It will not be effective if the current combative and negative furor continues. Every manufacturer that complains about Speedo will run the risk of having their equipment being judged as inferior to that of Speedo.

Speedo's marketing strategy has captured the attention of swimming aficionados and supporters. It has received the endorsements of swimming's heroes and heroines; has received a huge amount of unquestioning and supportive media coverage that continues to spread the company's propaganda; and has raised the ire of competitors, which strengthens its dogma further. This very effective marketing exercise is worthy of examination and emulation because it has been utterly successful.

Despite Speedo excelling in the marketing and propaganda arenas, it is still necessary to determine the truth about bodysuits and swimming performance. The following sections of this article attempt to do that.

People Believe

Why do people readily believe dogma and propaganda? It is a characteristic of humankind that has been repeated in the past and to this day in the acceptance of religious and political dogma and most commonly the tricks of the advertising trade. Acceptance of swimsuit-manufacturer dogma follows a similar manifestation. Christopher Hitchens commented on this characteristic as follows:

"It is not snobbish to notice the way in which people show their gullibility and their herd instinct, and their wish, or perhaps their need, to be credulous and to be fooled. This is an ancient problem. Credulity may be a form of innocence, and even innocuous in itself, but it provides a standing invitation for the wicked and the clever to exploit their brothers and sisters, and is thus one of humanity's great vulnerabilities". (p. 160-161)

The willingness of people merely to assume what has not been proved occurs frequently. The importance of evidence is recognized only sometimes. Where would humankind be if drug companies were not required to demonstrate objectively and repeatedly that their products have specific effects without harmful side-effects? One can imagine the consequences if every form of "snake-oil" was allowed to be marketed without restraint. On the other hand, the belief that bodysuits are performance-enhancing, in the absence of any objective evidence, has been accepted by swimming's masses.

The sheer scope of new information about a myriad of topics seems to desensitize the public about the need for proof of claims. The clever production of deceptive infomercials is one of the most insidious contributions of the Information Age. This phenomenon is prevalent in the domain of swimming bodysuits.

In sport, the role of sport science has been accepted as important for sporting success, although it has never been shown convincingly to be important. When a product associated with an important activity is dressed in the reported aura of science and "scientists" discuss "their" science, a willing public usually believes these manufactured authorities and follows the advertising message. And so it is with the second generation of bodysuits. The media write about them and the buzz-word around swimming pools is that serious competitors must have them.

It is now time to sit back and look at the evidence and actions involved with the marketing/promotion of bodysuits.

Speedo and other manufacturers claim the structure and materials of their "fastskin" [1] suits are based on science. With the first generation (2000-2008) of bodysuits, it was very difficult to obtain the claimed scientific evidence because of possibly exposing patent-protected exclusive manufacturing and technological knowledge. That prevented objective scientific evaluations of the "science" being performed. It also was difficult to obtain samples of suits upon which to conduct valid scientific analyses. At best, scientists were able to co-opt swimmers who had been issued with suits and perform tests with them (see previous articles in this journal). Independent research results have produced contradictory findings that suggest most assumptions underlying manufacturers' claims about bodysuits were spurious and possibly unfounded [2]. The introduction of full bodysuits in 2000 did not produce any general swimming performance benefit (Stager, Skube, Tanner, Winston, & Morris, 2001). If universal expected benefits existed, across the board improvements in swimming times should have occurred. Annual product announcements of further and added performance benefits were not supported by evidence or performance effects. The marketing claims of manufacturers seemed more likely to be dogma than substantiated facts.

Over time, rumors and facts surrounding the "science" that accompanied the development of bodysuits emerged. It was reliably reported that the shape of Speedo suits was based on the structures of two models, a male and a female. It is illogical and unscientific to generalize results obtained on a gender-specific datum to a larger gender-specific population. However, that appears to have been the case with Speedo's first generation bodysuits.

Science is required to be a public affair. It also is required to be objective, reliable, accurate, and have some external validity for relating to larger populations and/or phenomena. The bodysuit craze in swimming appears to be mostly an hysterical response of the masses to cleverly presented propaganda. It is a remarkable example of marketing of products without accountability for any claims.

There are a few published research studies using bodysuits. However, because bodysuits are used does not mean the research context is appropriate for validating their use in competitive settings. Studies have often measured a variety of factors related and unrelated to competitive swimming performances. Summaries of the more salient research factors and results follow.

Performance. Studies have only been performed on first generation bodysuits.

Only the most recent publication reported any performance improvements. One in five studies indicating benefits from this form of equipment hardly is an endorsement. It would be prudent to be skeptical of any claim that bodysuits generally are performance enhancing. At best, a few individuals might derive a benefit.

Energy and Physiological Effects. Energy savings while wearing bodysuits could suggest that swimming performances would benefit. It is hypothesized that less energy expended translates into performance improvements. However, there are equivocal findings as to whether energy/physiological benefits are gained from bodysuits. Unfortunately, studies that employ a control/comparison group have used conventional suits worn by unshaved swimmers. It is generally conceded that unshaved swimmers in traditional suits perform slowest and with low economy.

Only one of four studies using bodysuits reported beneficial energy and physiological effects. It would be spurious to claim any beneficial effects as a positive outcome of wearing bodysuits.

Flotation. If flotation was improved from using bodysuits, the energy cost of keeping up/streamlined would be less than when wearing a traditional (non-floating) swimsuit. The evidence with regard to buoyancy benefits is equivocal.

It would seem that flotation is not a consistent beneficial characteristic of bodysuits. However, as the suits become wet through use, this characteristic, if it existed, would disappear. Because of that time dependent feature, it is likely that flotation would affect short rather than longer events.

Passive Drag. Passive drag normally is evaluated by towing a prone still swimmer through water. Occasionally, a flume is used while the swimmer maintains the still position. Passive drag is a minor force in competitive swimming. When resistance is measured by towing on a rope, only profile drag is assessed. That will lead to a finding of lower resistance on the surface and higher resistance underwater (Jiskoot & Clarys, 1988). But, that would not be the same result as would be obtained with active swimming. Passive drag importance, usually inferred from the prone-still floating position, is diminished when a swimmer undulates the body (as in butterfly and breaststroke) or rotates about the horizontal axis (as in crawl and backstroke). Generalizing from passive drag measures to complex competitive stroking performances at best is a dubious action. [Readers are advised to be cautious when reading of passive drag reduction as being an important selling point behind any form of swimsuit.]

Active Drag. Tests of swimmers in a constant glide position yield measures of passive drag. Tests of swimmers actually performing a swimming stroke yield much more realistic estimates of resistive forces (Toussaint, Hollander, van den Berg, & Vorontsov, 2000; van der Vaart, Savelberg, de Groot, Hollander, Toussaint, & van Ingen Schenau, 1987). This latter measure is termed "active drag". Active drag is difficult to determine directly because the forces that act on the swimmer must be measured without disrupting the natural swimming movement. An exact way of doing this has not been found. However, the method used by Toussaint et al. (2000) is considered to yield very good estimates of active drag. To measure effects on active drag, swimmers must be consistent in technique and effort when swimming with and without the bodysuit. Estimates of drag resistances are more useful using this procedure than are measures of passive drag.

Shaved or Unshaved Skin. All studies comparing conventional/traditional swimsuits to fastskin suits were conducted on swimmers who were unshaved. Perhaps the most relevant datum in the Chatard and Wilson (2008) study was buried in one of the tables and not discussed. It reported a study by Sharp and Costill (1989) that showed the energy reduction in swimming in a shaved body condition was twice the reduction reported by Chatard and Wilson for either the full or lower-body fastskin suits. As well, shaving produces a beneficial effect on all performers. Wearing a bodysuit requires adaptation, does not guarantee performance improvements, and has differential effects on individuals. Despite the reported benefits on a number of factors of experimental suits, those benefits are only in reference to unshaved conventional-suit swimming. It is likely that bodysuits are not as beneficial as shaved swimming because no published study using fastskin suits approaches the consistent energy cost benefits of swimming with body hair shaved. Relying on one study (Sharp & Costill) as the evidence favoring shaved skin may seem dubious but it is the effect consistency and magnitude of that condition across all swimmers that warrants its advocacy. Bodysuits do not approach those qualities. The modern intrusion of manufacturers to sign-up/pay swimmers and teams to wear their products negates the possibility of evaluating the performance characteristics of different attire conditions in modern champions in competitions. It could be that modern swimming performances remain below optimum because bodysuits are not as beneficial for traveling through water in competitive swimming races when compared to shaved traditional-suit clad swimming (a claim frequently made by Alexandre Popov). This author proposes the hypothesis that the best condition for competing in swimming is with the largest amount of shaved skin presented to the water. That possibility is discussed further below.

The contention that shaved skin is the effective surface for swimming is supported by the fact that some outstanding performances have been recorded by swimmers wearing the minimal form of the Speedo LZR Racer – for men the hip-to-knee version and for women the open back-to knee form. In those cases, the swimmer has more uncovered than covered skin. One could contend also that world-records and top performances occur independent of the type (i.e., the proportion of covered skin) of suit – the only commonality between them all being the brand name.

Generally, the research on first generation bodysuits has been unflattering to the claims of manufacturers. It is a pity that so many performers have bought into the spurious propaganda of unsubstantiated performance benefits associated with this form of unimpressive equipment.

The second generation of bodysuits, heralded by the introduction of Speedo's LZR Racer, has once again spurred controversy over their use and effects. Fantastic claims have been made by the manufacturer, the media, and swimmers. An association of the manufacturer with NASA scientists appears to be sufficient to sway the opinions of many that the latest suits are actually the products of science. However, there have been no published research articles involving the second generation of bodysuits (i.e., post-2007).

The NASA "science" has not been made available in public or peer-reviewed forums. Based on the history of Speedo's "science" with the first generation bodysuits, one has to be skeptical of the claims of scientific development for this latest product. An immediate concern is provoked by the NASA connection. It seems that NASA primarily is interested in the performance of rigid objects (e.g., wings, rockets) in dynamic environments (varied and or constantly changing environments such as atmospheric air). Occasionally, NASA scientists have ventured beyond their research mediums and given opinions about what might be the scientific bases or mechanical factors involved in sports (such as why a spinning baseball curves in flight [3]). It is unknown at this time what the intentions of NASA were with regard to competitive swimming. Any association would appear to be remote and/or speculative.

For understanding swimming, the NASA model is likely to be inappropriate. Swimming differs markedly from rockets, fixed wings, and other solid objects in atmospheric flight. It involves a dynamic swimmer, a constantly changing non-symmetrical object, performing in a fixed medium (to all intents and purposes the water in a competitive pool is not [supposed] to be moving). The movement dynamics and velocities of objects in swimming differ greatly to most other activities involving movement through fluids. When understanding the mechanics of dynamic objects moving through a fluid, for swimming it is more relevant to study the actions of penguins and seals, both of which propel themselves with forward appendages much like human swimmers. To a certain degree, polar bears and Asian elephants when swimming also exhibit clues about appropriate mechanics for humans to propel themselves through water. As well, factors such as body coverings which may hinder movement are also better understood by studying such animals. However, the often compared tail-driven fishes are more irrelevant than relevant for studying the mechanics of human propulsion through water.

A distinction is made here; NASA research methods probably are not all that relevant for understanding swimming and its "equipment" whereas looking at penguins, seals, etc. is, offers more relevant interesting possibilities.

4. Simple Science Can Be Valuable

[The discussion of science here is limited. Many other facets appropriate for swimming and swimming apparel have been discussed elsewhere in this journal (see previous articles in this journal).] Studying creatures that propel themselves through water with their forward appendages can present information and provide observations that are meaningful for understanding swimming and the roles of surfaces of swimmers. This section will look at some of those phenomena, particularly as they relate to natural (e.g., skin) and unnatural (e.g., bodysuit) surfaces in competitive swimming. The phenomena discussed will be limited to those which can be discerned with the naked eye.

Penguins' Tales

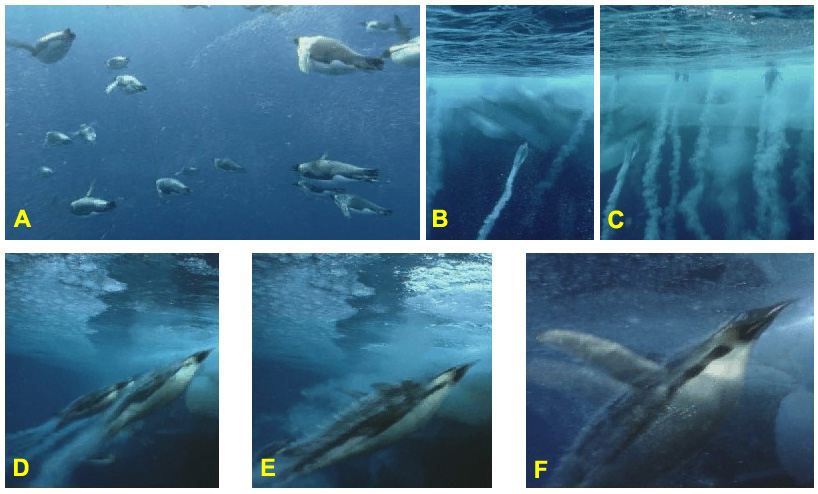

When an object moves naturally through a fluid (e.g., water) the fluid flows around it following its shape. When natural conditions change, the fluid breaks away from the shape and creates turbulent flow. What determines whether a shape is followed is the shape/contours of the object, the nature of the object's surface, and the velocity of the object. This is best illustrated by looking at various aspects of Emperor penguins swimming (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fluid flow around Emperor penguins while swimming at different velocities.

Figure 1 is divided into six panels.

The point behind this illustration is that it shows several features;

Turbulence is a problem because pressure in turbulence is less than in smooth/still water. Thus, when a penguin has turbulence following it as well as rear-oriented turbulence along its body, the drag pressure is from the bird's front to the back, which opposes the intended direction of travel. Surface and trailing turbulence should be minimized if forward progress is to be maximized.

Some of Speedo's Claims

Speedo has claimed that its bodysuits reduce both surface and form drag. [4]

The initial release of Speedo's bodysuits featured a textured fabric that was claimed to emulate sharkskin. The implication was that having a surface that mimicked a shark's skin (which species of shark was never divulged) would result in less surface drag for a competitive swimmer, that is, the swimmer would progress through the water with less resistance caused by the swimmer's surface. The covering of the total swimmer was claimed to be an improvement over the resistance caused by any skin. That benefit has never been shown in any practical or scientific arena. The sharkskin/fastskin surface persisted with slight modifications throughout the life of the first generation of bodysuits.

The role of surface resistance perhaps is overplayed by Speedo. Surface (frictional) resistance/drag is only active when the surface causes turbulent flow as the fluid follows the object form (see Figure 1 panel A). Once flow separates from the form (e.g., leaving the chin), surface drag no longer is in play as the surface in a drag pocket does not cause resistive frictional drag (See Figure 1 panels D-E and Figure 3 panel A for a good illustrations of this phenomenon). When separation occurs on a swimmer's chin, there essentially is no frictional drag on the surface under the chin or on the neck. Pockets of turbulence that cover a swimmer's surface negate the formation of frictional drag over that area. Given the poor hydrodynamic shape of the human body, there are many asperities and angular changes on the surface that cause fluid separation (e.g., all aspects of the face, depressions on the torso, between the legs, etc.) at certain velocities. It is opined that superior swimmers have better and smoother shapes that allow them to progress through water at a higher velocity without causing water to separate at angular changes on the body surface. Thus, the total body surface of a swimmer will not cause frictional surface drag; only that portion of the surface that entertains frictional flow will. This contrasts to the surface drag of a ship or boat, such as a racing eight, where surface drag is as much as 80-85% of total drag forces. This reduction in frictional drag surface on a competitive swimmer is one reason why frictional resistance, when measured, is such a small proportion of total drag (~3%) and also explains Clarys' (1976, 1979) findings of proportionally low frictional resistance measures.

The small amount of frictional resistance in human swimmers is also another reason why swimming in fluids of different density (e.g., fresh vs. salt water) does not generate differential times although in theory and according to swimming folklore, they do. If a swimmer's total surface area was included in calculations of resistance, inferential errors would result. Gettelfinger and Cussler (2004) showed swimming velocities in guar gum syrup and water to be similar. The very large difference in viscosity between the fluids was minimized by the small amount of actual frictional surface of the swimmers and some exploitation of increased viscosity by developing propulsive forces. The main point behind the discussion on surface resistance is that it is minimally important and should always be considered secondary to more appropriate fluid mechanics principles (Huijung, Toussaint, Mackay, Vervoorn, Clarys, de Groot, & Hollander, 1988).

Speedo also provided raised seams (see Figure 2) that were supposed to "channel" water flow in a beneficial manner. The reasoning behind this inclusion would seem to be dubious at best. The seams introduced marked surface deviations on the suit which would interfere with oncoming fluid flow. They would cause accentuated separation at the collision point. That would increase form drag. The asymmetrical pattern of the seams would produce drag pockets in various directions, the effects of which have never been determined. The seam ridges would increase the difficulty of a swimmer's progress. While swimmers move forward in a relatively straight line, their movements are complicated further by rotations about the horizontal axis (particularly in crawl and backstroke) and added vertical oscillations (particularly in breaststroke and butterfly stroke). Added to swimming stroke dynamics are a variety of flow disruptions of movement direction alterations that occur during the non-stroking skills of turning and diving as well as intermittent movements such as breathing. It is highly likely that suit contours (surface patterns and seam-ridges) would add resistance in the performance of those skills. [Speedo apparently has recognized the faulty engineering of the seam-channels and not included them in its second generation (LZR Racer) bodysuits. They even tout the absence of seams as an advantage in their latest suit.]

Figure 2. Swimmers Matt Dunn (on the left), Susie O'Neill, and Michael Klim wearing an early version of the Speedo Fastskin bodysuit with its obvious seam ridges and full-body coverage.

The second-generation Speedo bodysuits also are claimed to re-shape a swimmer's body by remodeling body bumps and firming up loose skin oscillations that might occur in some swimmers as they progress forward. These questions have to be asked:

Figure 2 also provides a clue about the suspect science involved in the concept and development of bodysuits. The suit surface is supposed to assist the swimmer to slip through the water with greater efficiency than without. That means the arms and lower legs in the bodysuit would be more slippery than if those anatomical parts were uncovered. However, that is the opposite of what is desirable. Modern techniques of champions clearly show that the complete arm is the surface that is involved in developing propulsion. As well, the lower legs and feet are responsible for developing counterbalancing forces for arm actions in some strokes and propulsion in others, particularly breaststroke. To develop forces in water, a swimmer's propulsive surfaces need to be as rough ("sticky") as possible and inhibit as much as possible any water flow around them. It is the non-propulsive surfaces that need to be least resistant while the propulsive surfaces need to be maximally resistant. Thus, for the suits depicted in the Figure, if their surface characteristics performed the way they were advertised, swimmers would have diminished arm-pull and kicking force production. ["What were they thinking?"]

Examples of Possible Errors

It would be helpful to consider evidence about the effects of bodysuits. In this discussion, the consideration will be limited to the fabric, which in Speedo's case was supposed to reduce surface drag. Initially, the first generation bodysuits will be considered since many are still worn by serious competitive swimmers. This discussion employs the principles evidenced by the phenomena of flow around Emperor penguins discussed above.

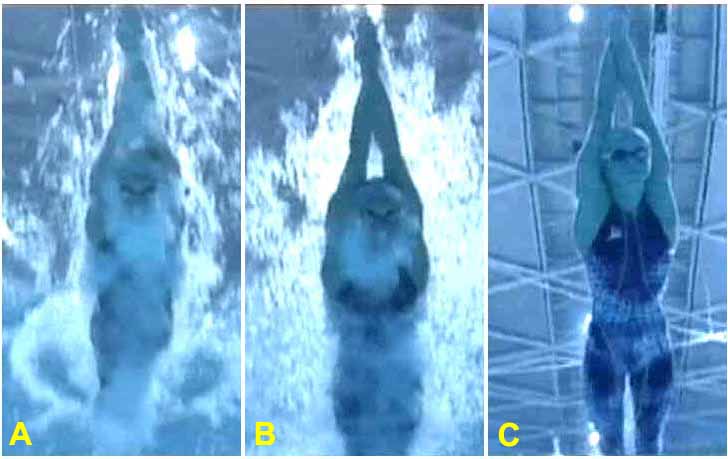

Figure 3 illustrates changes in resistance that occur with decreasing velocity. This set of panels shows the sites and amounts of separation that are produced after entering the water following a dive (O'Donnell, 2004).

Figure 3. Changes in resistive turbulence with decreasing velocity (adapted from research conducted by the Western Australian Institute of Sport (O'Donnell, 2004)).

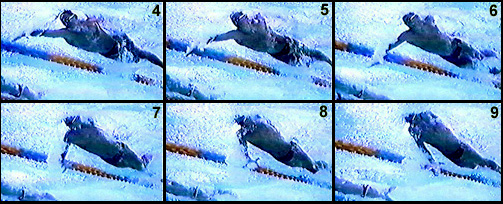

Just how much excessive surface resistance can be produced by these swimsuits is shown in Figure 4. It depicts Larsen Jensen swimming a 1,500 m race. Almost the total surface of his suit shows added resistance caused by the fabric and/or its knit. The local surface-caused turbulence covers the whole suit (down to the feet) except for the elasticized insert under the arm. One has to wonder how much better is this suit's surface than an unshaved swimmer's body at this particular velocity?

Figure 4. Larsen Jensen wearing a 2004 version of the Speedo bodysuit exhibiting increased surface resistance caused by the suit.

Figure 5 illustrates Janet Evans swimming in the Barcelona Olympic Games 800 m race that she won. She is wearing the standard Lycra suit issued to the USA team. In panels 22 and 23, there is no turbulence on the suit's surface. The white patch on her chest is the manufacturer's logo. There is no evidence of excessive turbulence being created by the face or other parts of the body (best seen in panel 23). In panels 19-21, turbulence created by the propelling arm and the turning of the head to breathe prevents a clear consistent picture of the suit. The Figure shows that in 1992, this swimmer's suit did not produce unnecessary drag nor did parts of the body. The clarity (lack of surface-caused turbulence) of Janet Evan's suit in panel 23 should be compared to that of Larsen Jensen in Figure 4.

Figure 5. Janet Evans swimming in her 800 m gold medal race at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

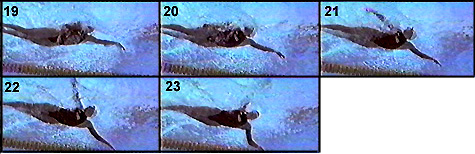

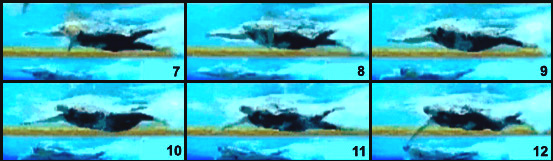

Figure 6 shows Alexandre Popov wearing a conventional Lycra brief swimsuit as he won a silver medal in the 50 m final at the World Championships in Perth in 1998. Two features are noticeable about the surface of the swimmer. The chest and shoulders and brief swimsuit do not create turbulence. Panels 7-9 illustrate clear surfaces suggesting that water is flowing over the surfaces without exaggerated disruption. This set of pictures indicates that the body contours and conventional suit do not create "drag resistance turbulence that needs reducing" (a reason given for the production of and marketed need for full length bodysuits).

Figure 6. Alexandre Popov swimming in the 50 m final at the 1998 World Championships in Perth, Australia.

Figure 7 illustrates Larsen Jensen (wearing a full length bodysuit) competing against David Davies (wearing a waist-to-ankle suit). Jensen's suit creates considerable turbulence as it did in Figure 4. As well, with his face looking forward rather than down, turbulence is created from the separation that occurs at the top of his cheeks. It can be assumed the face-turbulence mixes with the suit turbulence in this picture.

By contrast, David Davies' shaved body does not create turbulence. As well, the texture of his lower-body suit (manufacturer unknown) does not create much turbulence. The partly clad Davies carries markedly less disrupted water along with him than does Jensen. Jensen paid an "energy price" for adopting the bodysuit used in this event.

Figure 7. Larsen Jensen (closest) and David Davies competing in the 1,500 m at the Athens Olympic Games.

Figure 8 depicts Jodie Henry early in her gold medal 100 m race at the Athens Olympic Games. The full bodysuit she is wearing does not create nearly as much surface resistance as shown in the previous Figures. It is believed that this suit did not have the woven pattern in its structure of the type that generates excessive surface friction as in the case of Larsen Jensen. Of particular importance is the development of surface resistance in the lower-abdomen/upper-thigh area. The conventional suits of Janet Evans and other swimmers depicted in the How Champions Do It section of the Swimming Science Journal do not cause similar turbulence. An hypothesis that arises out of this phenomenon is that Lycra suits were better coverings than the "engineered" bodysuits. However, that possibility needs to be tempered because the manufacturer and individual both interact with the suits and cause different levels of resistance augmentation. One example is Hannah Stockbauer at the 2003 World championships. She did not display any augmented abdominal resistance at all (see her analysis in the How Champions Do It section).

Figure 8. Jodie Henry at 30 m of her gold medal 100 m race at the Athens Olympic Games.

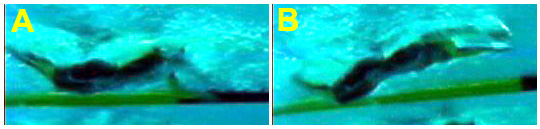

Figure 9 shows Petria Thomas during her gold medal 100 m butterfly race at the Athens Olympic Games. The excessive surface resistance caused by her full Speedo bodysuit clearly is evident. Bodysuits do not only effect crawl stroke but also butterfly stroke. Once Petria's head is down in the water (Panel B) the asperities of her face do not cause any notable turbulence. That feature suggests that the shapes of elite swimmers do not create unnecessary turbulence and do not require correcting (as implied with the LZR Racer bodysuit advertisements – see below in Figure 11).

Figure 9. Petria Thomas in the 100 m butterfly final at the Athens Olympic Games.

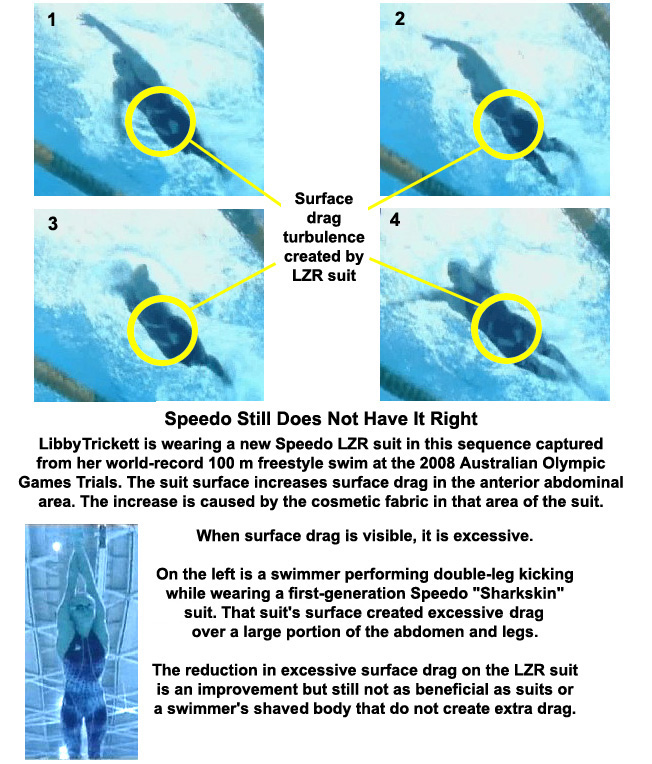

Figure 10 presents a comparison between the Speedo LZR Racer bodysuit worn by Libby Trickett during her world record 100 m race at the Australian Olympic Games Trials and the first generation Speedo bodysuit depicted in Figure 3. The LZR Racer still produces excessive resistance in the lower abdomen and is not that much different to the turbulence produced when Libby Trickett wore a first generation suit (see the analysis of her swim in 2005 in the How Champions Do It section of this web site). The Figure reiterates some points already made above. From this observation, it appears that the LZR Racer bodysuit is not much of an advance on the first generation suits.

Figure 10. A comparison of turbulence created by the Speedo LZR Racer bodysuit and a first-generation Speedo bodysuit.

One possible difference between the latest and previous generation of bodysuits is likely the amount of patterning on the suit. Figure 11 illustrates the patterned LZR Racer that was worn by many of the top Australian swimmers at the Australian Olympic Games Trials in March 2008. It retains a majority of its leading-edge surfaces as a knitted pattern. It is possible that the knitting still is rougher, and therefore generates more frictional resistance, than a smooth fabric (as illustrated above with Lycra suits and possibly those of other manufacturers) or shaved skin. While unusual knitting might look good (a desirable cosmetic effect), it could easily be detrimental to a swimmer's forward progression.

Figure 11. The Speedo LZR Racer bodysuit showing the amount of knitted pattern surface.

The basic principle underlying the assertion of value of bodysuits is that surface resistance can be reduced by decreasing disruption to fluid flow. With the first generation of Speedo bodysuits, disruption appeared actually to have been increased by the surface pattern and the seam-ridges. It is difficult to comprehend how a decision to employ those two structures in a suit design that was supposed to reduce resistance could be made. Their counterproductive effects are relatively obvious and simple to understand ["What were they thinking?"]. The surface disruption continues in the second-generation suits although possibly to a lesser degree.

The full bodysuits also have an adverse physiological effect in distance races. The normal direct cooling effect of water is hampered by the body coverage. Bodysuits inflate the thermal responses of swimming (Taimura, Matsunami, & Sugawara, 2003). Taimura and Matsunami (2006) reported there was a critical water temperature in competitive swimming (>29°C) when bodysuits cause increased thermal sensations of the body and head. Increased body temperatures cause performance to decline. Wearing bodysuits in distance swimming races in warm water is inadvisable because of their detrimental effect on performance, which is likely to be far more significant than any hypothesized ("marketed") physical benefit of the garments.

Grant Hackett set his world-record for 1,500 m at Fukuoka in 2001 wearing only a lower-body suit. Since changing to a full bodysuit (ostensibly for fiduciary gain), he has not approached his world record, although he has set the world-record for the "softer" event of 800 m freestyle. After completing a major 1,500 m event, Grant Hackett displays symptoms of mild heat stress, which would produce a performance decrement. Upon completion of a race Hackett's first action is to strip off the upper-body portion of his suit in the pool [with the latest LZR it is necessary to have another swimmer unzip it for him]. It would be interesting to see how much better he would swim 1,500 m if he returned to lower-body suits or even a regulation suit. It is unlikely he will break the 1,500 m world record again if he persists with wearing full bodysuits. The added heat stress prevents that. It might also decrease the possibility of his winning the 1,500 m for the third time in Beijing.

As with most performance principles, there is considerable individual variation in factors between individuals. Although the Taimura and Matsunami study showed that 28.9°C water did not promote bodysuits to cause heat stress symptoms, there are likely to be a number of individuals who will react adversely even at that temperature. A coach needs to monitor heat-stress reactions in each swimmer if they insist on wearing the bodysuit in distance races. Any symptom of heat-stress should be sufficient to reject wearing a full bodysuit. Heat stress also is increased when waterproof caps are worn, as is customary with national teams that display national and sponsorship logos (Matsunami, Taimura, & Sugawara, 2003).

What Science?

There has been little real science conducted on the effects of bodysuits of any manufacturer on competitive performances. Without access to sufficient garments and performers of a high standard, experimental work is difficult, if not impossible. The presentation here is preceded by a more in-depth discussion of the first generation bodysuits in (a previous article in this journal).

Although experimental evidence is meager, most public investigations have not shown support for the marketing claims of manufacturers. In this presentation, empirical evidence has been provided. Readers can draw their own conclusions about the phenomena that have been recorded in races. A summary of the points in this section follows below. It is an incomplete listing and only pertains to the major factors considered. Other items in this part of the Swimming Science Journal should be consulted for a more complete picture of what is known about bodysuits.

The above discussion relates only some factors that are and are not contemplated when bodysuits are promoted in marketing forays. Bodysuit use could compromise performance further with factors that have yet to be empirically assessed (e.g., the type of thinking and beliefs of the swimmer). Swimmers and coaches should be wary of extravagant claims of benefits of such suits although the media without much discernment continues to repeat positive marketing propaganda. Advocates of bodysuit use and in particular, for the manufacturer that has purchased their allegiance, should be disregarded.

There are real concerns, some of which have been researched, about the claimed benefits of bodysuits for competitive swimming performances. The results of those researches have been negative when manufacturers' claims have been evaluated. It is also possible that other factors exist that would further degrade the perceived performance value of bodysuits.

5. The Latest Speedo LZR Racer Bodysuit

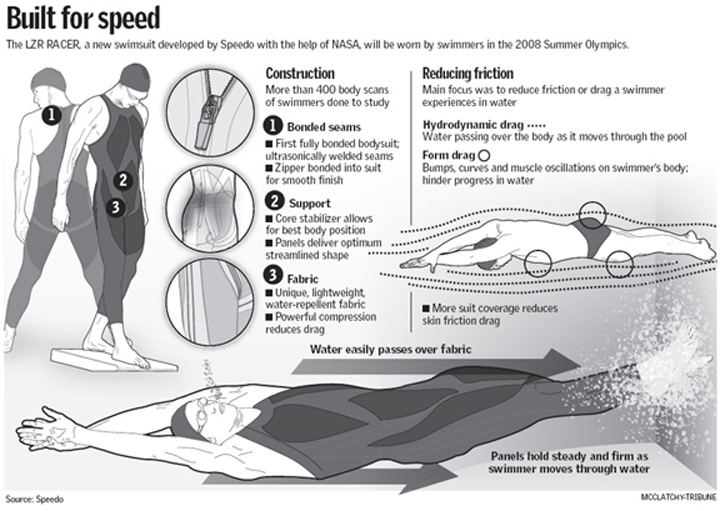

Figure 12 illustrates one advertisement for the Speedo LZR Racer bodysuit (reprinted from Almond, 2008). It is a worthwhile exercise to evaluate the content descriptions and claims. Because of the history of Speedo and other manufacturers in their advertising claims, it is prudent to be very skeptical of all claims and information included in advertisements.

Figure 12. A Speedo advertisement that indicates the structure and claimed merits of the LZR Racer bodysuit (from Almond, 2008).

There are nine major claims involved in Figure 12.

"More than 400 body scans of swimmers done to study [sic]". It is hard to envisage of what use 400+ body scans could be or whether they are representative of a particular group(s) of swimmers. When generalizing for effects or characteristics, there is a certain number that when reached exhibits a reliable quantification of the characteristic in question. Any more cases investigating the phenomenon would not change those values. There is a history of kinathropological studies having been conducted at world championships over the past 20 years. On those occasions, all aquatic sports and most of the performers were assessed for a variety of structural and performance characteristics. Mostly, those studies did not evaluate as many as 400 athletes. Unless a public accounting of this large number and how they are incorporated into one or more studies is made available, it would seem reasonable to ask if this claim is a "marketing exaggeration".

"Bonded seams". The removal of seams from Speedo's bodysuits is tantamount to an admission that the design of the first generation bodysuits was faulty. Now, an absence of seam ridges is claimed to be desirable attribute of the LZR Racer.

"Support. . . Core stabilizer allows for best body position. . . Panels deliver optimum streamlined shape". This claim suggests that swimmers need some external support to achieve a streamlined position. In the How Champions Do It section of this web site, there are two examples of Libby Trickett (known by her maiden name on Lenton in other entries on this web site) performing at a remarkable degree of excellence. One is in a first generation bodysuit and the other is in a LZR Racer (aspects of Figure 10 illustrate the LZR Racer bodysuit). With or without a LZR Racer bodysuit, the swimmer is able to maintain an effective and admirable streamlined position. For most champions, maintaining a streamlined body position is a characteristic in all strokes. It is asserted that this controlled rigidity along the horizontal axis is a learned technique feature that is not reliant on any outside support mechanism or notable strength characteristic (the force required to hold a desirable posture in this fully weight-supported sport is quite small).

It would seem that an externally restricted rigid abdomen would interfere with the undulating body actions of both butterfly and breaststroke. If the rigidity is as influential as claimed, swimmers would have to exert considerable effort to overcome that stiffness to perform adequate technique features (e.g., hyperextension of the mid- and lower back areas in breaststroke). [It has long been recognized that bodysuits were undesirable for breaststroke and medley events, although they were worn in those strokes' events when swimsuit contracts required it or swimmers wanted their contracts renewed or extended.]

It can be imagined where a need for some postural support might exist. However, swimmers requiring that would be of such a poor performance standard that an expensive bodysuit would be equipment "overkill".

Two or more fabric knits, weaves, or types as panels on a suit violate a principle involving constant fluid flow. As a fluid moves across each different surface, there is an alteration in fluid velocity which increases turbulence. Simple, uninterrupted surfaces are best. Panels on the LZR Racer should be regarded as a weakness in design.

"Fabric. . . Unique, lightweight, water-repellent fabric. . . Powerful compression reduces drag". There are two different aspects of this feature. The first concerns the fabric qualities. Being lightweight, it would be hoped that the bodysuit would not absorb much water. That would prevent it from being an extra unproductive load on the swimmer, a detrimental feature sometimes reported about the first generation bodysuits by distance swimmers.

Water-repellent fabric. Of more concern is the water-repellent characteristic. It is worthwhile to consider this feature to a greater degree than others.

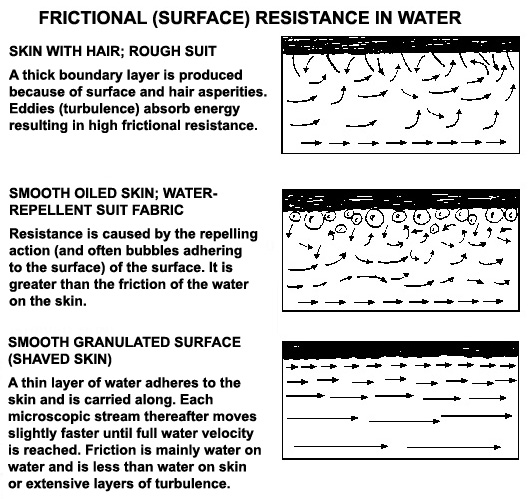

Surface characteristics have been an important feature for attention when seeking maximum velocities of, in particular, sail and rowing boats in competitive settings. Knowledge and understanding of desirable surface characteristics in water has existed for decades (e.g., Imhoff & Pranger, 1975). Figure 13 depicts three different surfaces and how they react in water (adapted from Rushall, 2003, p. 30.4).

Figure 13. Three different surfaces and how they react to water flow.

As water flows past the surface of a swimmer, friction between the surface and the water causes the fluid stream at the surface to stop. As streams move away from the surface, their velocities increase until the last stream flows in an uninterrupted manner. The different velocities promote turbulence. [It is unlikely that laminar flow would ever be exhibited.] The area between the surface and the first stream of uninterrupted flow is known as the "boundary layer" (Glenn Research Center, no date). The nature of an object's surface, and in this context a swimmer's skin and swimsuit, will govern the width of the boundary layer. The greater the width of that layer, the greater is the resistance. That feature has already been discussed above with regard to Emperor penguins and first generation bodysuits.

The upper panel in Figure 13 illustrates what happens to unshaved skin and the interference to fluid flow caused by hair and to a lesser extent dry raised skin flakes. When a bodysuit has a knitted pattern of ridges, turbulence is caused by the peaks and valleys in the fabric. That effect is illustrated above particularly in Figures 3 and 4. Energy is supplied by the swimmer to power the eddies. That is why it takes more effort to maintain a particular velocity when not wearing an efficient suit or shaved skin (i.e., the swimmer must move the body and a large volume of turbulent water which takes a lot of energy). It is desirable to remove the surface asperities so that the boundary layer is diminished.

The middle panel shows what occurs when there is surface tension. There have been a number of attempts to produce a surface that slips through water in a very easy manner. A logical, but incorrect solution was to oil the skin. The repellent tension between the fluid and the surface reduces the pressure on the surface often allowing small bubbles to adhere to the skin. Those bubbles act as asperities and increase the boundary layer and the cost of swimming. The same would happen with a fabric, such as that advertised by Speedo. The first generation fabric did produce small bubbles on the surface (see the illustrations of the Speedo fabric in another article on this web site ). The repellent nature on the outside of the suit would not be the optimal solution to reduce surface resistance. It is possible to remove adherent bubbles by physical force but still the repellent pressure gradient between the surface and the fluid would produce a larger than optimal boundary layer.

It is possible that the repellent function would serve a beneficial role between the skin and the fabric. In that restricted area, air bubbles could be trapped at the fabric surface and water displaced by their presence. That could produce a beneficial buoyancy effect inside this second generation bodysuit. The buoyancy would be a feature that would shift the suit closer to the beneficial quality of flotation that has been shown to exist with neoprene wetsuits. A cursory glance at the suits suggests that air would not easily pass through the fabric and so the possibility of flotation is increased. Nowhere does there appear to be any safeguard against "doctoring" the suits to ensure their flotation capacity is not increased.

The bottom panel illustrates the best surface qualities for a swimmer. Shaving the skin removes hair and rough skin flakes. If the swimmer also washes the newly shaved surface with detergent, then any oily areas would be cleaned. What happens is that the skin surface is not perfectly smooth but has a fine degree of roughness. Water is trapped in the small pits in the roughness. A fine layer of water would adhere to the skin surface. As a swimmer moves forward, the water-enshrouded body would slip through the water. The situation of water sliding on water is the most desirable circumstance for moving an object through the fluid. This illustrates the qualified principle that usually the smoother the surface, the less the resistance, but only up to a point. There is a narrow range of roughness that is better than very smooth.

Further explanation about ideal surface characteristics is warranted. A very smooth surface, and often a glossy one, is not as good as a rough or matte finish. The slight roughness creates friction that holds a layer of water and causes water to flow with the shape. A smooth surface does not "hold" water and it separates from the surface creating more turbulence. This feature is exemplified with golf balls. A dimpled (slightly roughened) golf ball will fly further than a smooth-surfaced ball. Racing yachts and rowing craft ideally do not have glossy smooth surfaces below the water line. They have a surface of minor roughness (often built into the paint) that is appropriate for the velocity zone that is likely to occur in a race.

The need for a minor degree of roughness is perhaps a reason why Speedo initially promoted a "sharkskin" knitted bodysuit. The actual implementation of that idea left much to be desired because there is a history of sharkskin simulation for objects progressing through water. In 1987-1988, 3M developed a sharkskin simulated surface as adhesive sheets. At the 1988 America's Cup, the surface material was offered to Dennis Conner's challenger and Iain Murray's defender 12-meter yachts. In the wind conditions off Fremantle, Australia, the yachts traveled between 6 and 10+ knots relative to the water. The sharkskin was supposed to maximize the surface conditions of an object in that velocity range. Only Dennis Conner covered his boat with the "sharkskin" for the final, which was won 4-0. It was that knowledge of sharkskin being appropriate for that velocity range that peaked the curiosity of this author to Speedo's claims for its "sharkskin" when the velocity of a competitive swimmer never approaches the range for which the 3M product was designed. Someone had to be wrong somewhere. Based on what has been exhibited over the years that first generation bodysuits have been available, the Speedo sharkskin was incorrect [assuming it actually was a replication of the skin of a species of shark – see the discussion of the Speedo fabric in another article on this web site ).

The ideal surface for a swimmer to incur the least surface resistance would be one that traps a very small layer of water on the skin and swimsuit surface so that the individual slides through water with the least resistant condition of water-on-water. It is this writer's opinion, which is supported by visual evidence provided in this article, that the current strategy of developing bodysuits is an erroneous ploy. Water-repellent fabrics will not produce the ideal surface for swimming attire.

Compression fabric. Compression fabrics have had valid and beneficial uses in medicine for many years. They are particularly useful for correcting some circulation conditions. However, there is considerable anecdotal (read that as meaning guess-work) evidence in sports that tight clothing provides support and prevents injuries. Adidas promoted that feature as one of the benefits of its early bodysuits: "Increased speed and endurance through the compression effect of Lycra Power which reduces muscle and skin vibration, cutting turbulence and fatigue, increases stroke accuracy, allowing more efficient performance" (advertised in the Swimming Times, September 1999). A quick search on Medline found no articles that evaluated compression materials and exercise performance.

Maitland and Vandertuin (2002) published a research account of the effect of compression clothing on muscular strength and endurance. Four compression clothes were custom fabricated for each of 15 athletes. Two garments were T-shirts that extended to the elbows, and two were shorts that extended to the knees. Compression was at 40 mm Hg. Performance was measured by repeated isokinetic testing of elbow and knee flexion. Compression was applied to one limb but not to the other (the control condition) in eight sets of tests. There were no statistical differences between compressed and uncompressed limbs in seven of eight tests. Left elbow extension displayed the only difference with performance being hampered by compression. A conservative interpretation of this study's results would be that the use of compression garments is a personal choice rather than because of demonstrable performance benefits. They coould not be worn to enhance performance.

There is also a minor physical downside to compression. If the soft tissues of the body are compressed, and muscles are soft tissues, then their density (specific gravity) increases. If a swimmer's specific gravity increases, he/she will sink deeper into the water and incur more resistance. That would serve to impede swimmers' progress, not help it. There likely is a very small trade off between the two factors. What benefits are gained, and the factual research says there are none, could be offset by the swimmer sinking more and incurring more resistance [particularly on the upper surfaces].

At present, there is scant to no research evidence that supports the belief that compression garments benefit sport performance. It certainly is true that the assuredness of Adidas' original and now Speedo's claims is not backed by scientific studies.

There also is a danger with compression garments being too stiff or tight. As was found by Maitland and Vandertuin, they could hamper some performances. There is a possible example of this having occurred in swimming.

Figure 14. Grant Hackett and Kieren Perkins in 2000.

Figure 14 illustrates Grant Hackett and Kieren Perkins in 2000. Perkins was the 1,500 m champion from the 1992 and 1996 Olympic Games. He was endeavoring to become the only swimmer to be a three-time winner of the 1,500 m in Olympic history. In that year, he chose to wear a total bodysuit (the questionable act of covering the arms and lower legs was discussed above). Hackett, unlike today, wore a waist-to-knee suit. In the Olympic race, Hackett won with Perkins second. A biomechanical analysis of the race showed that Perkins actually swam faster through the water but was too slow on the turns (where Hackett picked up his advantage). One could speculate that Perkins' previously good turns were hampered by the bodysuit. That aspect of his racing had never been a problem before 2000. One could interpret this action as being a poor decision strongly influenced by sponsorship and the advocacy of a questionable technology. [5]

Water-repellent fabrics that are sufficiently tight to compress the body are dubious qualities of a swimming suit. Their value for swimming performance enhancement has not been demonstrated.

"Reducing friction". As was discussed above, it is doubtful that friction has been reduced when compared to shaved skin but it does seem that the LZR bodysuit is less resistive than the first generation bodysuits [there seems to be a reduction in surface turbulence].

"Hydrodynamic drag". It is assumed that this term applies to all the resistive forces experienced by a swimmer. While the changes in structure (reduction in pattern area and removal of raised seams) of the LZR should be an improvement over first-generation bodysuits, the evidence of the amount of reduction producing a level of efficiency that surpasses other products, and in particular shaved swimmers, is purely speculative and likely advertising hype.

"Form drag – bumps, curves and muscle oscillations on swimmer's body; hinder progress in water" [sic]. Ostensibly, this is a claim that the suits "straighten out" a swimmer's body shape. While that might be an intention of the suit, its effect in top-level swimmers has not been demonstrated. As was discussed above, the curvatures of the body are not that much of a resistance-generating problem because of the slow velocity with which humans move through water in competitive swimming. One can imagine cases where a swimmer with a high body fat content and/or poor skin tone might benefit from compressing the skin surface. In today's elite swimmers, the majority of whom seem to be taller, straighter, and of respectable body-fat content than some time ago, any change in shape would likely be inconsequential. This advertising claim would be difficult to demonstrate and justify as producing a significant benefit.

However, there is a situation where the modification of a swimmer's shape is advantageous, the benefit being moderated by individual characteristics. The alteration of the cross-sectional volume of swimmers' breasts is a shape change that has been followed for many years in competitive swimming. It seems that the Speedo LZR Racer and other second-generation bodysuits do this modification very well. Now it is common to see female competitors make a final adjustment to breast comfort by pulling on the arm-level sides of suits immediately before mounting the starting blocks or entering the water when racing. However, no other physical adjustments have been shown to be necessary in the history of the sport or in its theory before Speedo suggested this feature in its advertisements.

"More suit coverage reduces skin friction drag". This is the third expression of the same claim within the advertisement. Covering the skin with a fabric does not reduce skin friction rather, it replaces skin friction with fabric friction. Although results are equivocal, research has shown that such a substitution sometimes is better than unshaved skin but not as good as shaved skin. With the improvements in this second-generation suit over features of first-generation suits, it is not hard to imagine the new coverage as being better than the old but still not the best surface for competitive swimmers in races.

"Panels hold steady and firm as swimmer moves through water" [sic]. This is perhaps another unnecessary selling point of the LZR Racer. As was discussed above, most fit individuals should be able to maintain a stable posture in this fully weight-supported sport as part of their stroking techniques – as a learned response. An external support system that could interfere with other aspects of swimming performance is unnecessary.

The claims made about the LZR Racer still contain exaggeration, speculative statements, and largely are unsupported by evidence. It is possible that Speedo has made some minor improvements in its equipment. While the first generation bodysuits might have represented three steps backward in the progress of competitive swimming, this second-generation bodysuit might have introduced one step forward. Only two steps to go to where competitive swimmers should be if this marketing ploy had never been introduced.

6. Psychological Considerations

In no discussion or research article, has there been a report of any attention being paid to the psychological impact of the situation surrounding testing and using bodysuits. When comparisons are made between preferred and non-preferred conditions, there are psychological variables that modify the responses of subjects. Unless those factors are taken into account, any pronouncement about one bodysuit being better than another would be misinformation. The experimental or testing situation would have biased results in favor of the condition preferred by the subjects. The main fact that studies are likely to reveal would be subjects' preferences, not actual effects of the equipment being evaluated.

Competitive swimmers very frequently are bombarded with advertising propaganda, others' opinions, and self-perceptions of the viability of bodysuits for successful racing. The almost constant barrage of information of varying quality and reliability shapes the beliefs of swimmers about the value of bodysuits. The strengths of those beliefs vary according to a number of factors [which will not be considered here]. Rather than diverge and enter into a detailed and lengthy discussion about belief formulation, existence, and effects on performance, this discussion will look at some of the more obvious situations that arise with regard to the swimming equipment used in important competitions. Those discussed will be as follows.

The extent of research in swimming psychology is limited. However, with general topics such as positive and negative thinking, and negative self-fulfilling prophecy, the results of studies in a number of sports were considered. The results were consistent irrespective of the sport setting. It is reasonable to assume (generalize) the existence of the phenomena in swimming.

Negative and Positive Thinking

Negative orientations toward performance have been shown to have disastrous effects on performance (Catanzaro, 1989; Ming & Martin, 1996; Wrisberg & Anshel, 1997). Examples of negative orientations are worry, wishing one did not have to race, swimming so that others will not be let down, and trying to avoid a bad performance. What results from negative approaches is a different physiology to what would occur with a positive orientation. Negative athletes function less efficiently, fatigue more easily, and use different physiological ingredients in their exercise response than when they are positive (Taylor, 1979). One cannot perform the same amount of work under a negative "mind-set" as can be achieved when positive. Negative mind-sets will cause swimmers to function less efficiently, and alter the energy properties of a performance. The amount of negative thought content prior to and during a race determines a major portion of performance deterioration. If one thinks badly, one will perform badly.

Some common negative-reaction situations are when swimmers are denied access to perceived-beneficial suits, made to wear suits that are uncomfortable and/or interfere with the execution of techniques and swimming skills (e.g., because the team is contracted to a "less desirable" manufacturer), or placed in a situation that promotes negative reactions (e.g., the desirable suit tears when donning it for a race and it has to be replaced by an "old" or "training" suit). Events such as these promote strong negative reactions that dominate swimmers' thinking for some time.

Swimmers need to interpret every racing situation so that the purpose of competing is to achieve positive outcomes. An athlete striving to do things well in every race evidences a positive approach to racing. That will result in a swimmer exploiting the best physiology that training has led him/her to achieve. Believing that one's racing swimsuit is the best available and that it will foster the best performance capability of the swimmer is an essential feature of today's racing "culture". No matter what the brand of the suit, if the athlete believes it to be advantageous, an important part of a positive mind-set toward racing will be established.

Rushall and Shewchuk (1989) investigated the effects of deliberately thinking self-prepared positive thoughts while doing two different training sets in nationally ranked Canadian age-group swimmers. Performance improvements ranged from 1.39 - 2.13%. That effect is greater than could be expected solely from wearing the latest bodysuits. Anything that lessens the amount and/or intensity of positive thinking will likely cause swimming performances to diminish.

The effect that the positive belief has on performance (e.g., "this suit will make me perform my very best") generally is termed a placebo effect. Its existence supports a best performance. When it is absent, or even contrarily negative, performance usually is less than maximal. Thus, when swimmers approach very important races, all aspects of the preparation need to be evaluated as being positive "signs" for a successful performance. If a swimmer's equipment is viewed as being inadequate, performance will suffer.

There is evidence that placebo effects do occur in bodysuit research. Roberts et al. (2003) reported that when swimmers wore bodysuits in a research setting, their higher level of performance was achieved through elevated effort and metabolic cost. The extra effort accounted for the performance difference between the conventional suit and the Fastskin bodysuit. Alternatively, one could advocate that swimmers did not try as hard in the conventional suit. Whichever interpretation is favored, the study showed that the different suits elicited differential response efforts while trying to do best performances.

The control of the placebo effect (the effect of negative or positive expectations for and thinking about performance) is important in research when comparing the latest bodysuits to older versions and even conventional suits. Research results of some experimental conditions might be doomed to poorer performances or evaluations because of pre-trial beliefs in failure. A myriad of factors can affect swimmers' beliefs about an impending performance. No research studies or anecdotal reports of bodysuit developmental procedures have attempted to control for the placebo effect.

Negative Self-fulfilling Prophecy

Swimmers who believe they have little chance of achieving goals or being successful, are likely to perform at low levels. The psychological literature has shown that when an individual predicts a negative outcome it very likely will result (Dalton, Maier, & Posavac, 1977), particularly in competitive settings. Unfortunately, the reverse does not occur with positive predictions, that is, if an individual says he will be successful, success does not necessarily ensue.