HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

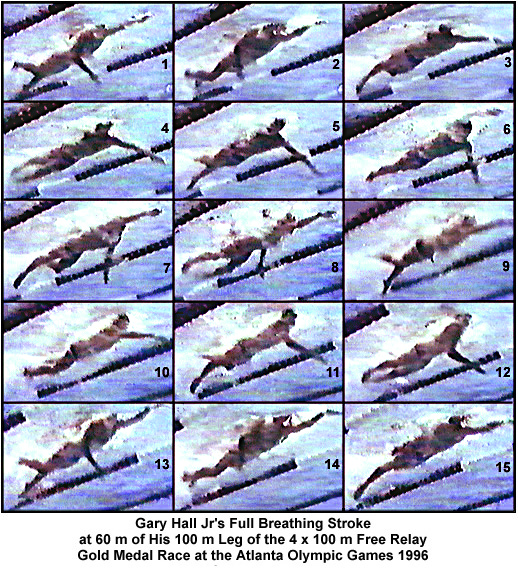

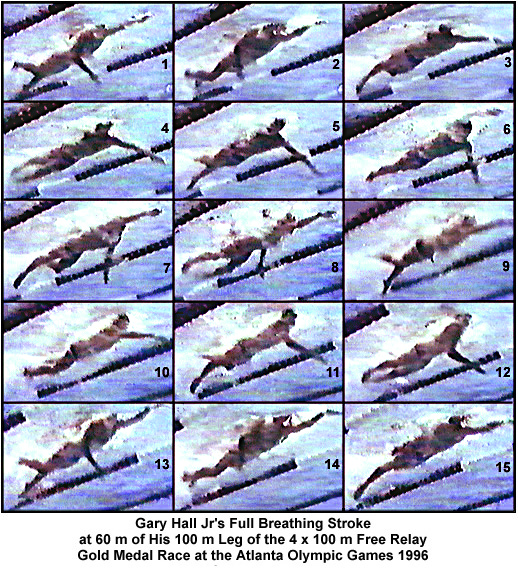

GARY HALL JR'S FULL BREATHING STROKE AT 60 m OF HIS 100 m LEG OF THE 4 x 100 M FREE RELAY GOLD MEDAL RACE AT THE ATLANTA OLYMPIC GAMES 1966

Each frame is .1 second apart. The split time for this swim was 47.45 seconds, the fastest ever recorded.

The analysis of sprint crawl strokes is separated from distance strokes for the following reasons.

- In sprint events the conservation of energy is not a great priority. Rather, it is more a matter of exuding as much energy as possible in the time it takes to cover the race distance.

- It has been shown that movement economy in sprint events is not as good as in distance events in cycling, running, and swimming. Consequently, accurate techniques, which are the hallmark of distance swimming champions, are not of great concern to the sprinter.

- Mechanical factors that are important for crawl sprint swimming might be different to those that are important in crawl distance swimming.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: The left arm is virtually straight when it enters the water. The right arm is in the middle of its propulsive phase. The head is raised slightly and begins turning to the right to breathe. The left leg has kicked to counter-balance the left arm entry vertical force component, the right arm pull, and also to assist in recruitment of muscle groups for postural stability and full reach. The right leg is bent ready to kick.

- Frame #2: The left arm immediately starts to bend at the elbow and the fingers start to point downward as it is depressed vigorously with the hand well away from the shoulder. The right arm continues its propulsive push back during its extension phase. The shoulders are rotating in time with the left arm entry and the right arm extraction. The head is turned for breathing. The right leg kicks to counter-balance the vertical force component generated by the left arm entry. The left foot is raised preparatory to kicking.

- Frame #3: The shoulders are rotated to the left to provide added momentum to the left arm downward press. This is probably as deep as the shoulder gets for if the shoulders were rotated more the time to achieve the rotation might be too long for the swimmer to achieve the fastest acceleration with the arm pull. The hips are not turned as much as the shoulders, a common phenomenon with a four- or six-beat kicking action. The left arm is bent slightly and still well in front of the swimmer. The counter-balancing right foot kick is completed. The head continues to be turned in the breathing action.

- Frame #4: The left arm is still extended well in front of the swimmer, is appreciably deep, and is slightly bent at the elbow. It has achieved a position that is deep and almost as far in front as possible so as to set-up the longest propulsive pull possible. The left leg kicks to assist the shoulders to stop rotating as well as counter-balance some vertical component of the left arm entry. The head is being turned back after inhalation.

- Frame #5: The path of the left hand has changed abruptly and is now propelled backwards with considerable vigor. The "long" arm position assists the hand and forearm to achieve greater velocity than would be possible if the swimmer had performed an "elbows-up" maneuver. The hand and forearm provide the propulsive surface. The left leg completes its kick and probably assists in muscle recruitment for initial force development with the left arm. The head continues to return.

- Frame #6: The left upper arm is adducted vigorously with the hand/forearm surface being pushed almost directly backward. However, this movement is not as effective as it could be because the elbow has moved very quickly to a new position while the propulsive surface has not moved as rapidly. That action is akin to a brief "letting-go" of the propulsive force. The shoulders are almost flat in concert with the approaching entry. The left leg is raised vigorously to prepare to kick while the right leg kicks. The head has almost completed its return.

- Frame #7: Full extension at right arm entry is clearly illustrated in this frame. The right leg has kicked to counter-balance the right arm entry vertical force component, the left arm pull, and also to assist in recruitment of muscle groups for postural stability and full reach. The left arm has completed its range of effective adduction and is now extending at the elbow and still pushing backward. During this left arm propulsive phase, the hand has remained relatively deep on the end of a long arm (lever). The hand portion of the push is relatively horizontal. The left leg starts to kick to counter-balance vertical forces produced by the right arm entry.

- Frame #8: As the right arm presses down in a long extended position, the left leg kicks very vigorously to counter-balance the vertical force components. The left hand continues to push back and remains deep. That is an index of the directness of the propulsive forces that are created and is achieved despite having its origin on an upwardly rotating shoulder. The right leg is bending to prepare to kick. The right shoulder is rotated down to assist in positioning the musculature of the shoulder girdle to create force principally through adduction.

- Frame #9: The left leg kicks vigorously to counter-balance the right arm depression. The left hand has almost completed its push and is near extraction. The right shoulder and hip have reached their terminal rotation point.

- Frame #10: The right leg kicks in coincidence with the right arm pull. Consequently, the right hip is kicked/raised upward. The right arm pull is initiated by adduction of the upper arm.

- Frame #11: The hips are flat as the right leg completes a deep vigorous kick. The right elbow bends to allow the center of the hand/forearm propelling surface to be pushed directly backward. The left leg starts to kick to counter-balance some rotation forces created by the right arm propulsion. The profile of the face is raised forward.

- Frame #12: Direct right arm propulsion continues through adduction of the upper arm. The left leg kicks and the right leg is raised in preparation to kick. The head commences to turn to the right to breathe.

- Frames #13-#15: Actions which are described for frames #1-#3 are repeated.

The long arm position during propulsion of the crawl stroke sprinter provides a greater radius of rotation and therefore, greater distal velocity for the arm. The sprinter's speed is assisted by this more difficult and exhausting long arm pull.

Gary Hall, Jr's obvious stretch forward under the water provides an opportunity for his arm's propulsive surface to create force over the longest distance possible. That contributes to his propulsion achieving the greatest possible amount of body acceleration.

To be able to achieve the stroke rate and propelling surface velocity that is needed to be a top sprinter, the shoulder rotation is less in magnitude than is seen in distance swimmers. That is most likely because such rotations are relatively slow, particularly since they involve stopping to change rotational direction. There is insufficient time to perform any larger movement. At least the latter half of the arm-propulsion phase is achieved with the shoulder being rotated upward which refutes the popular misconception that crawl swimmers perform as much as possible on their side.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.