HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

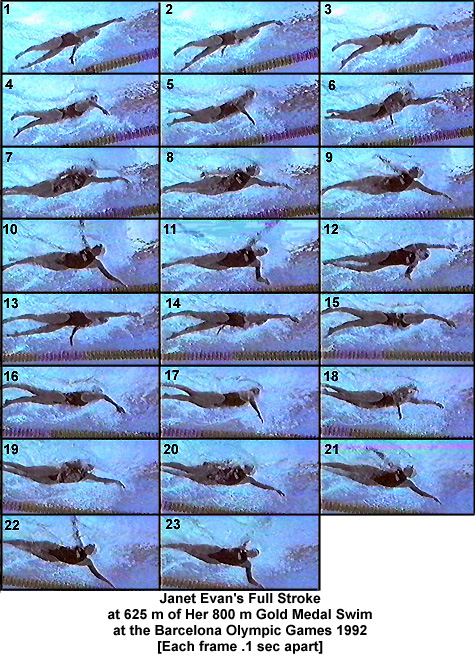

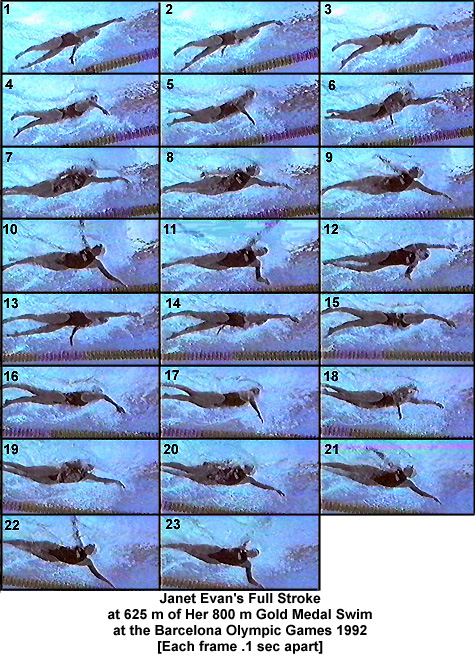

JANET EVAN'S FULL STROKE AT 625 m OF HER 800 m GOLD MEDAL SWIM AT THE BARCELONA OLYMPIC GAMES 1992

Each frame is .1 second apart. The swimmer breathes at the end

of each right arm pull.

Notable Features

- Frame #1: This picture illustrates a feature of most top crawl-stroke

swimmers. The right arm entry is made at full stretch (no underwater

gliding) and is accommodated by a very linear posture in the total

swimmer. The upper alignment of Janet Evans' arm, body, and leg

is almost a straight line. Of particular importance is the head

position. This is known as the "swimming blind" position

as the profile of the face is parallel to the water surface, that

is, the water line is well above the hair line and the eyes look

directly at the pool bottom. This position is achieved by many

crawl stroke swimmers, particularly females, and is characteristic

of Jenny Turrell (1970s) and today's Brooke Bennett.

- Frame #2: Evans' pull starts immediately with flexion at the

wrist and the shoulder fully elevated. The inertia of her recovery

and its transition into re-positioning for propulsive pull is

counter-balanced by a left leg kick.

- Frame #3: The right hand feathers to the outside as the arm

flexes more and medial rotation of the upper arm commences. The

reason for this short-lived feather is not obvious but could be

a brief movement to counter-balance a part of the left arm recovery.

The kick in this position is not propulsive but rather, creates

a drag force to counter-balance the still predominantly vertical

forces developed by the re-positioning movement of the right arm.

The counter-balancing keeps the hips high and streamlined.

- Frame #4: Janet Evans commences to lift her head which was

a trademark of her swimming style. It is hard to justify this

initial and subsequent head movements as being beneficial. To

counter-balance the vertical forces created by the head lift the

forearm/hand combination, which constitutes the propelling surface,

creates vertical as well as horizontal force components. It is

at this stage that an "elbow-up" position is sacrificed

to accommodate vertical forces.

- Frame #5: The swimmer's head is emerging above the bow wave.

The left leg is raised to prepare to kick. The propelling surface

of the right arm is primarily aligned in a horizontal plane although

the body is not sufficiently angled on its side to produce a long

adduction movement at the shoulder.

- Frame #6. The left arm has very rapidly entered the water,

the wrist flexed, and vertical forces immediately created. This

occurs in concert with the turning of the head to the right to

breathe. Hip roll to the right side is initiated as is a right

leg kick.

- Frame #7: Both arms are creating small forces at this time.

The left arm, particularly on the hand surface creates a small

propulsive component as part of the resultant force of the arm.

The right arm is at the end of its propulsive phase and is initiating

an exit. The head is being returned to the water which is counter-balanced

by the continued right-leg kicking action. Hip roll to the right

continues.

- Frame #8: Janet Evans has continued to keep her face profile

to the right. Normally, one would have anticipated that by this

time the face would be returned to a position which would promote

"swimming blind." The hips have continued to turn to

the right as the right leg continues to counter balance the left

arm press.

- Frame #9. The left arm continues to press down counter-balancing

the right arm recovery which has a large vertical component because

of its almost straight position. The arm positions are virtually

opposite each other. The face profile is still to the right.

- Frame #10: The face/head movement is "locked" in

phase with the right arm recovery. This slow movement contravenes

popular notions of breathing actions being independent of arm

positions and occurring outside of the effort phase. The right-leg

kick is completed. The forces created by the kick and the vertical

component of the left-arm pull support the long, high, almost

straight right-arm recovery. The shoulders appear to be turned

to the right to a much greater degree than the hips, possibly

because of the need for the right leg to create vertical forces

(which would not occur if the hips were rolled to the same extent

as the shoulders).

- Frame #11: The face is turned to look forward and down with

a very rapid movement. The left arm applies forces directly backward

while the hips, and shoulders rotate and the right arm sweeps

forward with considerable speed.

- Frame #12: The fingers of the right hand are just entering

the water. The left leg starts to kick to counter-balance this

movement. The head starts to look down.

- Frame #13: The position in frame #1 is attained. The head

seems to be oriented slightly more forward as opposed to directly

facing the bottom of the pool. The shoulder is elevated to produce

the longest reach forward possible. The remaining frames give

a slightly different view of the actions already described.

- Frames #14-#23: The consistency of Janet Evans' stroke cycle

is striking.

Janet Evans' stroke is not symmetrical. It contains significant

vertical movements which require allocating potential propulsive

forces to counter-balance those extended and unproductive aspects

of the stroke. In theory, there is much that could be improved

in the technical aspects of this swimmer, and yet, this is the

style of an Olympic Champion, albeit one who is performing considerably

slower than when at her peak four years earlier. It is not known

whether the "faults" commented on here were responsible

for Janet Evans' slowing since the previous Olympic Games.

A notable aspect of this stroke is one that is similar between

many high-rating female distance swimmers. The length of time

taken in recovery is very short. The entry is ballistic using

the inertia of the recovery to "blast" through the re-positioning

phase of the underwater stroke, to get to a powerful propulsive

phase in a very short time. The speed of her recoveries is such

that when one arm appears to finish its propulsive movements,

the other arm commences its propulsion. This produces a desirable

feature of the swimmer being subjected to an almost continuous

propulsive force. There are no long delays between force applications,

and none to the same extent as those exhibited by great male swimmers

(see Murray Rose, Keiren Perkins, and Evgenyi Sadovyi on this

web site).

It is possible that the physiological differences between males

and females, particularly in the way that oxygen and glycogen

are used for endurance metabolism, supports female swimmers performing

this high rating, short power-application-phase form of swimming,

something which could possibly not be tolerated by males.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.